I’ve decided to devote my Solid Ground articles in the weeks to come to an in-depth look at chaining. It’s a basic mechanic of which everyone is at least marginally aware, but it’s one of the most frequently misunderstood processes in the game. Before we embark on chaining, though, it’s not a bad idea to brush up on some terms that can leave players confused: namely, activation and resolution, and cost and effect.

The activation of an effect and the resolution of that effect are two separate parts of the effect, and they certainly influence how an effect fits into a chain. “Activation” means declaring your intent to use an effect and paying any necessary cost associated with it. This can include flipping a face-down spell or trap card face up, announcing you will use a monster effect, or playing a spell card from your hand. These are all ways to activate an effect, and paying life points or discarding a card are examples of costs. When you activate an effect, you simply indicate that you intend to use it, and pay any associated costs. If the effect is part of a chain, activation means you’re merely adding the effect to the chain.

“Resolution” happens later, and it’s a separate part of using the effect. Resolution is when you actually carry out the effect, after it has been activated and your opponent has been given the chance to respond to the activation. If the effect is part of a chain, resolution won’t begin until all the effects have been added.

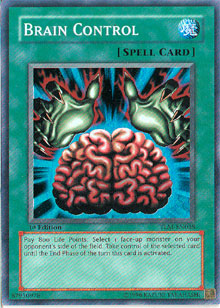

As you can see, activation and resolution are two distinctly different parts of every effect. When it’s laid out in black and white, it seems very straightforward—so where does the confusion come from? Effects with an activation cost are the biggest source of confusion, because players sometimes tie the “cost” and the “effect” together in their minds. Since the cost “happens” at activation, it seems logical to them that the effect should happen then as well. Players figure, “Well, I just paid 800 life points for Brain Control, so why don’t I immediately gain control of my opponent’s monster?” The problem here is easy to see when you actually consider what’s going on, though. Let’s take a closer look at costs, how they tie into activation, and how they can be confusing.

If you’re going to use an effect that requires a cost, that cost needs to be paid when you activate the effect. In fact, paying the cost is part of activating the effect. There’s many a slip between activation and resolution, though. Even though you activate that effect and pay the cost, there’s no inherent guarantee that you’ll go straight to resolution if that effect goes on a chain. Since the cost is paid as part of activation, and activation is clearly separate from resolution, it necessarily follows that the cost is not part of the effect.

We’re clear on the reason why you don’t get a card’s effect at the moment you pay the cost. Now we need to differentiate between a cost and part of an effect, which isn’t always easy. Being able to recognize between a cost and a part of the effect will help clarify how the card actually works, so it’s definitely important.

There are some “clues” that can help you tell what is what. Generally speaking, if the card tells you to “Pay (insert number here) Life Points,” or “Discard a card,” that’s usually a good indication that it is a cost and not part of the card’s effect. If a card tells you to do something first, before you can use the effect, that’s also most likely a cost. Lightning Vortex, Breaker the Magical Warrior, and Brain Control are all examples of costed effects. You have to pay the cost to activate the effect, and if the effect does not resolve, you don’t get your payment back. However, if the effect tells you to pay life points, discard a card, or perform some other action after an effect happens, it is never a cost—it’s part of the effect. Cards like Power Bond, Graceful Charity, or Snatch Steal are good examples of cards with a “cost-like” effect. The life point penalties and card discarding happen after the effect. Therefore, they’re part of the effect and not a cost required to use it.

There are some “clues” that can help you tell what is what. Generally speaking, if the card tells you to “Pay (insert number here) Life Points,” or “Discard a card,” that’s usually a good indication that it is a cost and not part of the card’s effect. If a card tells you to do something first, before you can use the effect, that’s also most likely a cost. Lightning Vortex, Breaker the Magical Warrior, and Brain Control are all examples of costed effects. You have to pay the cost to activate the effect, and if the effect does not resolve, you don’t get your payment back. However, if the effect tells you to pay life points, discard a card, or perform some other action after an effect happens, it is never a cost—it’s part of the effect. Cards like Power Bond, Graceful Charity, or Snatch Steal are good examples of cards with a “cost-like” effect. The life point penalties and card discarding happen after the effect. Therefore, they’re part of the effect and not a cost required to use it.

If you’re going to chain your cards correctly, you need to understand the distinction between all these parts of an effect (activation from resolution, cost from effect) so you’ll understand what you’re responding to, what you can respond to, and why you can or can’t respond to something. The last thing you want to do is make a flawed or illegal move that reveals your cards to your opponent and backfires, risk incurring a penalty if you somehow manage to mangle the game state past redemption, or build a deck around an incorrect interpretation of a card.

Understanding the difference between activation and resolution is also going to help you use your card resources more wisely. Knowing that activating a card won’t guarantee a resolution if your opponent can chain to it helps you better assess risks. For instance, you’ll be much more likely to activate Premature Burial when your opponent has a clear spell or trap zone than you would be if he or she had a few sets there. You don’t want to risk a set Dust Tornado or Mystical Space Typhoon if you can avoid it.

Hopefully this article helped make things a bit clearer for anyone who’s had trouble with these terms. Now we’re ready to spend a few weeks intensively studying chaining, right? The most basic of game mechanics, if incorrectly understood, can cause a host of problems in a duel, beginning with deckbuilding errors and working all the way up to misplays and unintentional self-sabotage. Stick with me over the next few weeks, even if you’re sure that you know it all. You never know what insights you might pick up from a good close look at a vital part of the game.