The Yu-Gi-Oh! TCG cannot be played consistently well without the ability to make good decisions. Learning how to repeatedly make accurate decisions in the presence of complex situations is a huge prerequisite for success. However, keeping this up is a very difficult task. We have certain psychological tendencies that influence us in ways that can cause silly thinking and terrible mistakes. This week, I’ll go over a few of our psychological tendencies, discuss how they apply to the game, and make some suggestions on how you can avoid their effects.

Aversion to Loss, Consistency, and Self-Deception

Consider this short story . . .

You are preparing your deck for a Shonen Jump Championship and you have practiced at least 20 hours prior to the event. You feel that your deck is ready and it has "proven" that it can consistently perform well against the expected matchups. The night before the event, you’re playing some practice games just to "warm up." About 20 games into the process you find that you’re not winning as much. All of a sudden you start to panic. You ask: "Is there something wrong with my deck? Did my friend just get lucky?" Naturally, you disregard your previous inquiries. "Nah, my deck should work out just fine. There’s no need to improve it just because I lost a little bit." The following morning, well into round 3, you find that you’re having more trouble than you expected. "My deck should be winning without much trouble, why am I having such a hard time?"

Now you’ve made it to round 6. You’ve won so far despite having a few near-losses here and there. Unfortunately, round 6 is where your luck took a sudden turn for the worst: you’ve lost the match. You say: "No big deal. It’s only one loss. I’ll make up for it by winning the next four." In the next round you lose again, but by a small margin. You begin to doubt yourself and question your deck’s consistency. "There must be something wrong with my deck. It tested perfectly: why am I still losing matches?" At this point you’re a bit angry. In your mind, you’ve been dealt an injustice by lady luck and you deserve to win because you’ve practiced so hard, spent X amount of money, and traveled X miles. You’re supposed to win right?! Why is this happening? "It’s just not fair!" you say.

Since we naturally want to avoid losing or even feeling like we’ve lost, we tend to disregard many obvious warning signals trying to tell us that something may need to be reconsidered. We want to be consistent with our decisions and actions. When we commit to something, we have a natural inclination to stay the course. We will consciously ignore any information that tells us that we may be on the wrong path, even if it costs us greatly to stay on it. We tend to believe that a little more time, a little more money, or a little more effort will make things better. You have to be very careful with this behavior. However, this is not always a bad thing. We are pre-programmed with that pattern of behavior because it is often beneficial to act that way. Commitment and consistency are two important factors of a successful relationship with another person for example.

Since we naturally want to avoid losing or even feeling like we’ve lost, we tend to disregard many obvious warning signals trying to tell us that something may need to be reconsidered. We want to be consistent with our decisions and actions. When we commit to something, we have a natural inclination to stay the course. We will consciously ignore any information that tells us that we may be on the wrong path, even if it costs us greatly to stay on it. We tend to believe that a little more time, a little more money, or a little more effort will make things better. You have to be very careful with this behavior. However, this is not always a bad thing. We are pre-programmed with that pattern of behavior because it is often beneficial to act that way. Commitment and consistency are two important factors of a successful relationship with another person for example.

The first paragraph of the short story paints a sad picture of a great many players who fall prey to the same mental trap: avoiding asking the potentially unsettling questions that may yield answers they’re not comfortable facing. One good way to prevent massive errors in judgment is to not avoid questions like these: they will improve your overall win/loss record more than you think. Consider the possibility that your main and side deck choices are not as tuned to the metagame as you believe. Think about the possibility that your testing partners may not be as good as you or may play in a manner that is atypical of the competition at the next event. Also, take into consideration the fact that your deck may not be as consistent as you think. It is possible to have more than a few good draws that lead to potentially misleading results about the overall strength of your deck.

It’s important to think carefully about the consequences of being wrong. Ask: "What if I am wrong? Can I handle being wrong? What will it cost me emotionally or financially?"

Underestimating the Influence of Chance and Undesirable Outcomes

We play a card game that has a good deal of chance involved, and sometimes luck is in your favor the night before the tournament. Just because you’ve had excellent draws prior to the main event doesn’t mean that the same fortune will reappear the next day. There isn’t a record of how lucky or unlucky you have been in the past. The odds are all the same regardless (Assuming your deck is unchanged and your playstyle remains relatively the same). If your deck loses 20% of its games to Dark Armed Return, then that 20% may repeat itself multiple times in a row. Over the course of 500 games or so, your loss ratio to Dark Armed Return will average out to 20%, but there may be instances within the span of 500 games when you lose ten to twenty times in a row. You are more likely to win over time, but you can still have losing streaks.

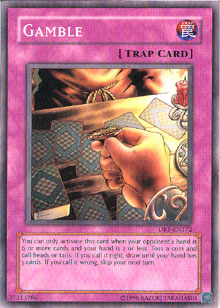

Everyone knows that the odds of flipping head or tails is almost 50/50. However, if you took the time to flip a coin 100 times in a row, you may flip ten heads in a row, then flip a few tails, and back to heads again. Did the odds change? No. They’re still the same. The odds are unchanged during each independent event. Getting five in a row does not give you better or worse odds of flipping heads or tails. Understanding how luck really works will help you develop a much better attitude toward the inevitable misfortunes that occur in competitive play. The win ratios that you glean from using the standard testing techniques should only be used to infer what the odds of your victory are: it is not a guarantee. Take that information with a grain of salt.

Everyone knows that the odds of flipping head or tails is almost 50/50. However, if you took the time to flip a coin 100 times in a row, you may flip ten heads in a row, then flip a few tails, and back to heads again. Did the odds change? No. They’re still the same. The odds are unchanged during each independent event. Getting five in a row does not give you better or worse odds of flipping heads or tails. Understanding how luck really works will help you develop a much better attitude toward the inevitable misfortunes that occur in competitive play. The win ratios that you glean from using the standard testing techniques should only be used to infer what the odds of your victory are: it is not a guarantee. Take that information with a grain of salt.

Normally, we get upset when we lose in situations we classify as "pure luck." I’ll be the first to admit that I hate losing when it’s out of my control. There are things you can do to curb the odds more in your favor. Here are some thoughts:

Do the best you can to build a deck that is as mathematically consistent as possible. The greatest leverage you have against the luck factor is to make sure your deck’s math is consistent enough to minimize the instances in which luck can turn your match sour.

There are many factors that influence your win/loss ratio versus any type of deck, but in terms of pure chance, always remember: chance has no memory. It does not care how many times you win or lose.

If your deck isn’t working during testing and you find yourself getting frustrated, then I suggest you give it a rest and call it a night. There’s no use in trying to make alterations to your deck while you’re in the midst of a quiet rage.

Test games and tournament games occur in two mutually exclusive environments.

Consider the possibility of being wrong about your individual card choices and plays. Think about the possible undesirable outcomes that may result from your decisions: don’t narrow your vision to only outcomes you want.

Most of the time putting in a little more effort, money, or time won’t make it better. Knowing when to put a bad idea, situation, or relationship to rest is very helpful and very wise. Consider the costs.

This is merely an introduction to the complex web of traps and modes of thinking we engage in. I encourage you to think about these concepts and how you can avoid faulty thinking. Thanks for reading! I look forward to delivering Part 2 next week!