From the prospective of a developer, Avengers was one of the more challenging sets to produce. There was no single issue that was as tricky as those that we’ve seen in other sets, such as balancing willpower in Green Lantern Corps. Before that, introducing the hidden area into the game with Marvel Knights was possibly the most daunting task that we’d undertaken. Some fundamental assumptions were challenged—mostly those regarding a player’s ability to take down foes through attrition and to be safe with the initiative. While each set has presented its own challenges, Avengers was particularly ambitious in just how many new areas it explored.

While some ideas in this set have been explored on a couple of cards per team in the past, the following concepts had been relatively unexplored as major themes for any team:

Leader

Reservist

Playing towards an empty hand

Resource point spending

Rewarding your opponent

Eleven non-unique characters with the same name

Breakthrough replacement

Characters improving as the game progresses

On top of these traits, there were plenty of other themes that were re-examined, both in the set as a whole and on specific teams. These themes include team-ups, team attacking, bonuses while ready, reinforcement gaining and removal, equipment, “cannot be targeted” effects, off-curve builds, and effects that KO stunned characters—and no doubt, there are others that I’m forgetting.

In the upcoming weeks, I’ll discuss many of these themes from a developer’s perspective. While some of the themes were introduced largely because they were unexplored areas, it’s important to note that many of these themes were the result of brainstorming ways to specifically improve gameplay and diversify play patterns. Some of the highest priorities that we tackled in this set include:

Encouraging off-curve strategies

Encouraging multi-team decks

Improving play for suboptimal hands (for example, character-heavy or non-character–heavy draws)

Encouraging players to expend cards earlier in the game

Increasing the relevance of formations

Can you tell which of these themes were intended to help a particular goal, and which ones we thought were merely cool? I’ll address this question in my future articles, as well as discuss some more subtle issues and areas that we’ve tried to improve. As always, feel free to suggest other areas of gameplay that you’d like to see us improve upon and let us know specifically what you liked from this set and from others. As I go through these topics, bear in mind that we were also intent on establishing a well-rounded card pool for Modern Age and cranking powers up a notch for Golden Age. With that said, let’s move on to leader, which is the first of our new keywords.

Leader

Leader was a particularly thematically appropriate keyword for this set, given the team rosters. It wasn’t a matter of whether or not we would use this keyword, but rather of what it would do. When the leader keyword was merely a fledgling idea in Mike Hummel’s mind, I believe it was largely meant to team up adjacent characters. This fell in line with wanting to encourage players to try multi-team decks. This idea lasted through development to the final card pool on one character for each of the four largest teams. Helmut Zemo à Citizen V, Warmonger, Egghead, Captain America, Steve Rogers, and Hyperion, Mark Milton bear a power that corresponds to that initial idea.

Leader was a particularly thematically appropriate keyword for this set, given the team rosters. It wasn’t a matter of whether or not we would use this keyword, but rather of what it would do. When the leader keyword was merely a fledgling idea in Mike Hummel’s mind, I believe it was largely meant to team up adjacent characters. This fell in line with wanting to encourage players to try multi-team decks. This idea lasted through development to the final card pool on one character for each of the four largest teams. Helmut Zemo à Citizen V, Warmonger, Egghead, Captain America, Steve Rogers, and Hyperion, Mark Milton bear a power that corresponds to that initial idea.

After some discussion on how leader could work, it was decided that leader would not be an abbreviation for a more complex power, like the way that reservist stands for the phrase, “You may recruit this card from your resource row. If you do, you may put a card from your hand face down into your resource row.” Given the complexity of some keywords in recent sets, and knowing that we wanted to use the reservist keyword in this set, we decided to opt to define the leader keyword in a way that put very little burden on the player. The keyword interacts with our game in two straightforward ways. First, it lets a player know that this character has a power that relates to adjacent characters. Second, it’s a keyword that is referenced by other cards.

While I was initially going to devote the rest of my article to discussing the leader keyword, the topic has already been covered in some depth by Mike Hummel. As he states, we were cautious about the complexity and power level of having multiple leader characters in play at once. He also discusses how leader characters varied significantly in power level, depending on the initiative and on the presence of flight on your opponent’s side of the board. These were factors that weighed heavily on which powers we chose and on how those powers were developed. At any rate, I’d recommend reading Mike’s article (again) now that you’ve seen the whole set. Other than that nonsense about missing Danny, it’s a good read.

Reservist

For reasons discussed in the section on leader, we wanted to keep our keywords fairly simple. Being able to recruit a character from your resource row and then having the option to put a card from your hand into your resource row seemed to be about on the level of what we were looking for. There was some discussion of whether reservist in its current form would do enough for us. It was considered whether maybe the reservist keyword should highlight that it was usable in the resource row, and that there would be a variety of things you could do with that card.

Once I saw Mike’s idea to have the Squadron Supreme team focus on dumping the player’s hand, I couldn’t have been more sold on the initial idea for reservist. First of all, I was very excited about the idea of an empty-hand deck, and reservist was a perfect fit for that theme. Now you could hide your characters in your resource row—how else could you possibly expect to hit your curve with no hand? But besides promoting what I though was one of the coolest themes Mike had suggested, I felt the reservist keyword would push a couple of our main goals forward.

Once I saw Mike’s idea to have the Squadron Supreme team focus on dumping the player’s hand, I couldn’t have been more sold on the initial idea for reservist. First of all, I was very excited about the idea of an empty-hand deck, and reservist was a perfect fit for that theme. Now you could hide your characters in your resource row—how else could you possibly expect to hit your curve with no hand? But besides promoting what I though was one of the coolest themes Mike had suggested, I felt the reservist keyword would push a couple of our main goals forward.

First, I believe reservist holds a lot of potential for off-curve decks. Off-curve decks often run more characters than typical decks, in order to make sure they have enough 1- and 2-drop characters to hit those drops every game. I don’t have a lot of hard evidence to back up this generalization, but I’ll note that Adam Horvath’s winning Honor Among Thieves deck in PC Amsterdam ran 37 characters. Not to oversimplify the issue, but this is more characters than you’d typically see in a deck. While Adam Bernstein ran 36 characters in his winning Curve Sentinel deck at PCNY, most of the Top 8 decks ran closer to 32 characters. In a 60-card deck running 37 characters, you will have the following number of non-character cards, on average, at your disposal each turn, assuming there’s no additional card drawing or mulligans.

Turn | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Avg. # Non-Char Cards | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 6.1 |

Now if things always worked on “average,” there’d be a lot less complaining by one person following a game of cards. However, if you look at these numbers, there isn’t a lot of room for variance. I’m sure you’ve all been forced to put a character in your resource row on an early turn of the game, never to see it again. Often, it isn’t even an easy choice. Which drop do I risk missing? Which character will be more important on turn 4?

Let me digress here by discussing a second area in which I felt reservist would shine. Reservist has a lot of potential to alleviate those character-heavy draws. If you don’t have a non-character card to put into your resource row early in the game, a little luck might help you draw into some more non-character cards. By the time you want to recruit that character, you’ll hopefully be able to put a non-character card from your hand into your resource row. In this way, you can avoid having a completely “dead” card in your resource row. Yes, there are character cards that will sometimes go unused in the course of a game, but many of the most competitive decks have ways to use character cards in hand with the likes of Bastion or Titan’s Tower.

In contrast, character cards in your resource row are usually dead cards. There are very few ways to make use of a character card once it’s in your resource row. In the future, you shouldn’t be surprised to see us push this angle even outside of the scope of reservist characters, with cards resembling Mattie Franklin, LexCorp, In Evil Star's Evil Clutches, Ra's al Ghul, Underground Sentinel Base, Element Man, Manhunter Engineer, Sleeper Agent, and others.

Now, back to the topic of off-curve decks. Aggressive off-curve decks tend to burn through cards rapidly. Another way of looking at this is that these decks don’t have many cards to spare and cannot afford to have any dead cards. If the off-curve player puts a reservist in his or her resource row, that player’s avoided having a dead card, assuming there isn’t another copy of that character in play when the player would like to recruit that character later in the game.

On the last turn or two of the game, if the off-curve player runs out of non-character cards, he or she doesn’t even need to put a card from the hand into the resource row. That player might be lucky enough to put a swarm of characters out onto the board that had been acting as resources in the meantime. On the last turns of the game, players who choose off-curve decks are often living off the top off the deck to make another character play, and so an early reservist that the player was forced to put in the resource row can be a nice insurance plan.

One of the more exciting ways in which reservists may help provide an opportunity for off-curve decks isn’t within gameplay itself—it’s in deck construction. I believe reservists make it more reasonable to play more characters in a deck, so that you can reliably make your drops early in the game and yet not be in fear of playing dead cards in your resource row.

A final selling point for reservist characters was for low-resource decks. Because when you’re playing a reservist character from your resource row, putting the card from your hand into your resource row is optional, this seemed like a means of further encouraging the theme of having a low resource count, like we had explored on team like Emerald Enemies and on cards like The New Brotherhood.

A final selling point for reservist characters was for low-resource decks. Because when you’re playing a reservist character from your resource row, putting the card from your hand into your resource row is optional, this seemed like a means of further encouraging the theme of having a low resource count, like we had explored on team like Emerald Enemies and on cards like The New Brotherhood.

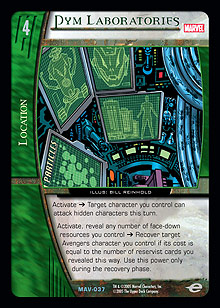

Okay, I haven’t talked too much about development per se. Instead, I’ve hit on many of the big-picture issues. In future articles, I’ll describe the balancing of cards that reference these keywords either en masse, like Wonder Man, Black Panther, and Pym Laboratories; or singularly, like Avengers Assemble! or Hulk, Gamma Rage.