Benjamin Disraeli, British Prime Minister from 1874–1880, was reported by Mark Twain to have uttered the potent quotable, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics.” While there has been at least one British citizen who can claim to have landed the title of Pro Circuit Champion, Disraeli would never have had a shot. I am a man of science. I am a peddler of statistics. Data-based decisions are almost always superior to decisions made based on a gut feeling or uneducated opinion.

Sometimes, statistics can be presented in a way that is misleading. Often, it is not the fault of the actual statistic; rather, the blame is best laid on faulty interpretation. Statistics are incredible tools. They allow you to achieve goals with maximum efficiency, they can reduce your workload, and they occasionally help you reach an end result that would not otherwise be obtainable. But they have some of the same limitations that other tools have: some are inferior and some are superior; if you use them incorrectly they can mess up your project; and they often rely on the skill of the operator for ultimate success.

Analysis and Synthesis

If you have covered the content of the previous six lessons, then you have begun to see a pattern. The statistical methodology presented in the first articles will not be enough for success. There is a method to my madness. In fact, the statistical methods were presented, and that information was followed up by guidelines that allowed those statistical outcomes to be interpreted.

I might be able to build a deck in which I land my perfect curve in close to 100% of my games, but that deck may win no games in a tournament. Simply hitting a curve is not as powerful as hitting a great curve. Hitting a great curve is not as powerful as hitting a great curve of characters with great tricks, and hitting both great tricks and a great curve may be inferior to hitting great characters and tricks specific to a great win condition. Rather than clinging to a strict regimen of character dropping, there must be an emphasis placed on game theory, card evaluation, and a deck’s win condition.

Statistics can be used for analysis, which is the process of taking something apart to study it. I love to break things. When I was a small (maybe never small, but young) child, I was a mini-hulk. I smashed tables, threw my brother through a window (all in good fun), and shattered my share of bones. I love physical sports. In college, I may or may not have thrown a flaming couch off a third-story balcony into a pile of fresh snow. As an adult, I am the kind of dude that takes things apart just to see how they work.

Statistics can be used for analysis, which is the process of taking something apart to study it. I love to break things. When I was a small (maybe never small, but young) child, I was a mini-hulk. I smashed tables, threw my brother through a window (all in good fun), and shattered my share of bones. I love physical sports. In college, I may or may not have thrown a flaming couch off a third-story balcony into a pile of fresh snow. As an adult, I am the kind of dude that takes things apart just to see how they work.

Analysis gives us the chance to deconstruct our ideas, our play, our assumptions, and the contents of our decks. Breaking things down into component parts is cool. The decks in Vs. System are like houses of cards or a giant set of Legos — they can go together in the most intricate or haphazard ways. If you grab the “right pieces,” you may be able to dominate your competition. My favorite part of building stuff, though, is tearing it down.

Reverse engineering can be used to steal valuable corporate secrets. If you take an invention and disassemble it, break it down, and begin to understand why it works, then you may end up with powerful new knowledge. There are no copyrighted deck ideas or trademarked strategies in this game, and we have access to many new inventions through the internet and playtesting with different individuals. Top 8 decklists from $10K events and Pro Circuits should be seen as a chance to glean new information. If you can analyze a decklist and extract its secrets, understand its synergy, or derive its win condition, then you will be able to apply that knowledge to the next deck you play or build.

In earlier lessons, we talked about the power of innovation. That power usually begins in an early analytical genesis. Players must first learn how to master the concepts of the game, and then learn to apply them to new situations, materials, or ideas. In most cases, you have to imitate before you innovate.

Once you are able to break down ideas and understand the workings of successful decklists and synergies, you may begin to enlist your own creativity in the more tender art of synthesis. Synthesis as applied to Vs. System may be seen as one’s ability to find unique, effective interactions in cards (as Mike Barnes does) or generate your own new school of thought (as West Virginian deck engineers do).

Playtesting groups and professional teams often house players who can both analyze and synthesize information, but they usually employ analytic aficionados and synthetic specialists. Bringing information together may not be my strength, but once I have a large data set, multiple pieces of information, or two years worth of metagame outcomes, I can make choices that are more effective. Growing up, my brother was more the type to put things together. He liked building the Lego towers and assembling the forts. I liked jumping off the table to see the pieces fly around the room. Now that I think about it, that is likely the situation that led to his adventure through the window.

As an adult, I do not get many opportunities to throw people through windows, but I do get ample opportunities to break down decklists and analyze tournament outcomes. I like taking card pools and looking for the pieces that fit, but I would rather look at successful puzzles that have been assembled and break them down so that I might solve similar puzzles in the future.

The Win Condition

One of the most relevant things to analyze in deck construction is the win condition. Does the deck expect a bunch of little characters to get together on a key turn to fight? Does the deck want increasingly bigger characters to battle until the biggest and baddest one is left standing after a veritable slugfest? Or does the deck look to secure victory with a collection of counters or multiple opportunities to burn an opponent? The win condition should be a compass for deck construction.

Popular decks have primarily relied on causing endurance loss through combat to achieve the “W.” There is a subset of key variables or establishing operations that may be necessary for achieving that endurance loss. Recent decks such as Ivy League have attempted to remove a player’s cards from his or her hand, and thus limit the number of resources and the size of characters that can be recruited. Other decks have provided weapons, tools, or bonuses to supplement undersized characters in combat, and yet others have relied on the tried and true strategy of bringing the “best fighters”— characters with the most desirable statistics—to the party.

There are alternative win conditions like Secret Six Victorious, but those decks have failed to shine in recent times and the most recent Ages. Whatever your choice, it is important to make the most of your card inclusions and evaluations relative to the end goal of the deck. My little buddy Tim Batow was chastising me just the other day for including a rather defensive-minded character in a very aggressive decklist. It prompted me to think about the recent Pro Circuit championship deck and a Sealed deck that I covered during a feature match in San Francisco. Anthony Calabrese’s Secret Society deck was a fairly “clean” and ultimately effective assembly of cards. His early game was intent on the destruction of some particularly troublesome 3-cost characters that dominated the metagame. The deck also focused on acquiring Dr. Fate’s Tower and the Fate Artifacts in order to make some defensive-minded characters even more defensive. The character selection focused on characters with abnormally high DEF stats in the 4- and 5-drop slots that allowed the deck to achieve its win condition: late game combat.

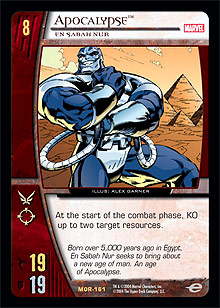

Jason Hager created a very defensive-minded deck during Day 2 play at PC: San Francisco. He acquired a solid 8-drop and used defensive plot twists and Hellfire Club characters to get to the later turns. While most people were winning games on turns 6 and 7, Jason was taking people a turn past their intended goals. In an environment where people were assembling turn 6 win conditions, Jason’s deck thrived by taking players to unintended places. Anthony’s PC fortune was built on the same principle. While the Good Guys and hyper team-attacking decks were trying to close the deal on turns 5 and 6, his deck dragged them into later turns to face much bigger problems than they were prepared to deal with. In the end, I noticed a theme. Over time, we have witnessed success with decks that take the opponent’s deck past its desired turn-count. More specifically, successful decks at PC: New York took the popular Curve Sentinels deck past the desired turn 7 kill and into uncharted turn 8 waters. Apocalypse was bigger than Magneto, Master of Magnetism, and the end result was some unfortunate late-game action for the typically curving Sentinels.

Jason Hager created a very defensive-minded deck during Day 2 play at PC: San Francisco. He acquired a solid 8-drop and used defensive plot twists and Hellfire Club characters to get to the later turns. While most people were winning games on turns 6 and 7, Jason was taking people a turn past their intended goals. In an environment where people were assembling turn 6 win conditions, Jason’s deck thrived by taking players to unintended places. Anthony’s PC fortune was built on the same principle. While the Good Guys and hyper team-attacking decks were trying to close the deal on turns 5 and 6, his deck dragged them into later turns to face much bigger problems than they were prepared to deal with. In the end, I noticed a theme. Over time, we have witnessed success with decks that take the opponent’s deck past its desired turn-count. More specifically, successful decks at PC: New York took the popular Curve Sentinels deck past the desired turn 7 kill and into uncharted turn 8 waters. Apocalypse was bigger than Magneto, Master of Magnetism, and the end result was some unfortunate late-game action for the typically curving Sentinels.

For your next tournament, it may be interesting to analyze the metagame. You may break down the decks and find a trend of games ending on turns 5, 6, or maybe 7. If you can find a way to take those decks to later turns, then you gain an advantage that has passed the test of time. Taking your opponents past their scheduled kill turn and into yours is almost always a great move. In turn, if the environment shifts to late game decks, then you may want to find a way to speed up your deck to find victory.

I have written two or three times about the importance of tempo. In the case of the late turn decks or early turn beaters, you must adjust your play style—in addition to your usage of resources and plot twists—to establish and maintain your selected deck speed. When taking your opponent to late turns, it can be important to use more defensive-minded tricks and characters. The Heralds of Galactus set offers a number of chances to gain endurance, exhaust characters, or keep characters from readying. In those decks, a stall or early board elimination strategy may pair well with late game characters, but if you blow all of your good defensive tricks or endurance gain too early, you may not see turn 7. In contrast, some decks love to do as much damage as possible in the earliest turns. These decks have had limited PC success, with the notable exception of Squadron Supreme. That deck encouraged players to dump their pumps early and fast because emptying the hand allowed the later game burn to be effective. In concert, the early endurance loss from combat and later endurance loss from burn finished the game.

For your homework, it would be reasonable to look at the upcoming metagame and think of decks that could extend the game into later turns. We are staring down decks like High Voltage, Teen Titans, and Good Guys. If you can take any of those decks into the very late game, then your advantage will grow with each resource you set. On the Sealed Pack side of the game, it may also be useful to analyze the powerful archetypes and deck builds that are possible. Do you like a turn 6 Kree kill or dropping the 8-drop fatty for the win? In each format, what mindset and tempo will you choose to fulfill your win condition?

Class dismissed.

Jeremy “Kingpin” Blair (7-drop, TAWC) is a card flipper and student of the game from the southeastern part of the United States. If you have constructive comments or questions, feel free to contact him at Tampakingpin@yahoo.com.