Step 5: Initial Set Design and Development

Step One: Getting Started

Step Two: IP Research and Picking Teams

Step Three: Art

Step Four: Set Mechanics and Team Dynamics

Design Bible

Part Eight: Initial Design and Development

Overview

In this part, R&D builds an initial set of cards as quickly as possible in order to test mechanics and team dynamics.

Questions on Initial Design and Development

What is the difference between initial design and later design?

What is the difference between initial development and later development?

What are the specific goals of our expansion with regards to initial design and development?

What is the methodology of building the initial set?

What strategies are there in designing the initial batch of cards?

What is the methodology of developing the initial set?

Thoughts on Initial Design

The big difference between initial design and development and later design and development is our goals. In initial design, we want to build a set of test cards as quickly as possible (often the card pool is only about 100 cards) in order to test raw concepts and the basic feel of the teams. Later design involves actually creating cards that will make it into the final file.

Initial development’s goals are to find out which basic mechanics are fun or interesting, and to explore the breadth and depth of the different teams’ dynamics. By “breadth and depth,” I mean how many mechanical concepts a team has available (breadth), and how many cards we feel we can or should make for each of those mechanical concepts (depth).

It’s important to understand what specific goals we have for our initial design and development because our goals can affect the way we create and test the initial set.

For example, in the initial design of the Man of Steel expansion, we wanted to see how many concepts translated well to the on/off feel of the cosmic mechanic. Therefore, we designed many more characters with cosmic than would make it into the final file. Similarly, in the early testing of the Marvel Knights set, we concentrated heavily on the concealed mechanic before looking at some of the more “normal” angles of the game.

The primary consideration when building an initial set of test cards is speed. We want to design a bunch of cards (usually around 110, which is the number of commons in a typical Vs. set) as quickly as possible so that we can move to initial testing. There are several methods we can use to design the initial set, each with pros and cons:

The Consensus Method

This method involves a group of designers working both separately and together, sharing ideas and brainstorming new ones. The lead designer acts as a moderator, often making the final call on adding a proposed card to the file. The strength of this method is that we can put in more discussion and debate on the front end, which means that cards that make it into the initial set are much more likely to end up in the final file. There are two problems with this method. One, it takes a long time, as debates over single cards can rage on past the point of productivity. Two, investing a lot of effort on individual card design at the beginning of the process can be wasteful when (as sometimes happens) entire mechanics get thrown out during testing.

The Lone Wolf Method

This method is the opposite of the consensus method, as it involves the lead designer pretty much creating the entire initial set on his or her own. The strengths of this method are that it’s about as fast as it gets since there’s no discussion or debate, and that the entire set will retain the lead designer’s single vision. The main potential problem with this method is that the lead designer is probably going to have to spend a lot of time working alone, absent from the previous set’s development process (but this is not necessarily a bad thing).

The Director Method

This method falls somewhere between the other two. The lead designer hands out design assignments to the rest of the design team and decides which proposed cards to include in the file, often altering the incoming suggestions to fit his or her overall vision. The strengths of this method are that, like in the Consensus Method, it gets the rest of the design team involved, but like in the Lone Wolf Method, it retains the lead designer’s single vision. The weakness of this method is that it requires the lead designer to take the time to assign appropriate tasks to the rest of the team.

It’s worth noting that while the Consensus Method is probably the biggest offender, all three methods run the risk of wasteful front-end investment if we spend too much time working on individual cards. This speaks to the point of how important it is to create the initial set quickly. It’s always easy to add new cards to the test file down the line, so it’s just not worth putting in too much time on any individual card this early in the process.

Another strategy to employ when creating the initial set of cards is to design bottom-up almost exclusively. As a quick review, top-down design involves looking at the flavor of the card first and then coming up with an appropriate mechanic, whereas bottom-up design involves creating a mechanic first and then assigning it to a card with appropriate flavor.

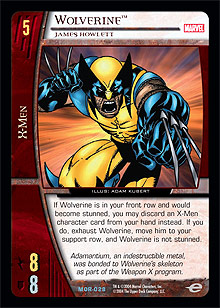

As an example of top-down design, if we wanted to give Wolverine a power that represented his healing factor, we could design a mechanic that allows him to shrug off a stun. An example of bottom-up design would be if we came up with a cool mechanic that allowed a character shrug off a stun, and then decided to put it on Wolverine because it worked well with the flavor of his healing factor.

As an example of top-down design, if we wanted to give Wolverine a power that represented his healing factor, we could design a mechanic that allows him to shrug off a stun. An example of bottom-up design would be if we came up with a cool mechanic that allowed a character shrug off a stun, and then decided to put it on Wolverine because it worked well with the flavor of his healing factor.

While top-down design and flavor considerations are a huge part of building a Vs. expansion, during initial design, it’s much more important to test raw concepts. Therefore, the lion’s share of initial design should be mechanics first or bottom-up. (This is not to say that the lead designer can’t try to match form with flavor, just that it’s not of primary importance.)

Another design strategy is to make sure that each team has plenty of cards intended to explore each of that team’s angles on the game. While it might seem like a no-brainer—“of course we need cards to test what each team can do”—at this stage of testing, we actually need many more cards of a particular theme than will make it into the final file. Really, this is just another way of saying we should try to design more cards than we’re going to use, so that we can cull the best ones and scrap the rest.

There are two main ways to develop the initial set of cards: Constructed and Sealed play.

Constructed development in the initial stages is similar to later Constructed development in that developers try out different archetypes to see what’s viable and/or fun. There’s less emphasis on breaking individual cards at this point and more concern about breaking entire mechanics.

Sealed play initial development is actually pretty different from Sealed development down the line. In fact, while it’s good to get a sense of how the core mechanics of the set feel in a Sealed card pool, a major reason to play Sealed with the initial set is to check out any cards that might have been overlooked in Constructed testing. Often when a developer has success with a previously under-used card in draft, he or she will try the card in Constructed.

At this point, we should have designed and developed our initial set of test cards. We should have a good idea of which mechanics are working out and how our teams are feeling.

Next Entry: Fleshing out the designs of the main teams and designing legacy cards.

Green Lantern Design Diary

Part Eight: Initial Design and Development

Last time I went over how we came up with the concepts for willpower, Constructs, and concealed—optional. I also talked about our initial plans for each team’s mechanical flavor. Now, it’s time to talk about how we created and tested the initial set of cards.

I chose to use the Director Method when designing the Green Lantern initial set. This was for a couple of reasons. One, Brian Hacker suggested that I run the show with more of an iron fist (like he had for the Marvel Knights set) because it was a much more efficient use of time than the Consensus Method (which is what we’d primarily used for the first four expansions). Two, I didn’t have time to generate the whole file myself (a la the Lone Wolf Method) since I was doing a lot of rules work on the Marvel Knights set.

Most of the initial set was created by Ben Rubin, Andrew Yip, Darwin Kastle, and me (with some help from other members of R&D). I designed most of the willpower cards hoping to get a better understanding of how much design space the mechanic afforded us (quite a bit it turned out). Ben Rubin was excited about a self-resource destruction theme, so I asked him to design a bunch of cards, which I ended up shaping into the Emerald Enemies. Andrew did a lot of work exploring wacky hidden zone interactions with the Anti-Matter team, and Darwin came up with some cool ideas for the Manhunters as well as working on a hodge-podge of random card ideas I’d ask for.

Typically, my design direction would be something like this:

“Hey Darwin, can you give me like ten non-character cards that involve putting cards from your opponent’s deck into his or her discard pile?”

or

“Hey BR (which is what we call Ben Rubin), I need a couple of 3-drops for the Emerald Enemies. One should let you KO its own resources. The other can do whatever you want (in theme).”

Here are some cards from one of the very first files I wrote up.

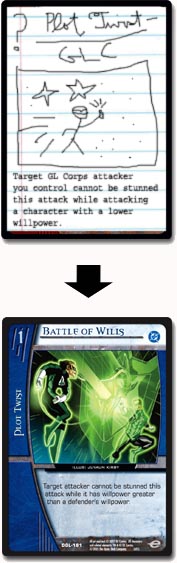

Plot Twist – GLC

Plot Twist – GLC

Target GL Corps attacker you control cannot be stunned this attack while attacking a character with a lower willpower.

I wanted to point this one out because it ties into one of the first principles about willpower we learned. Because only a small percentage of teams in the Vs. System would have access to willpower, we couldn’t really make cards that check your characters’ willpower against the willpower of your opponent’s characters because all too often, your opponent’s characters would have exactly zero.

But the above card (which would become Battle of Wills after we cut the team-stamp) was my attempt at making a fair willpower-comparison card. While we would probably never make a generic card that made your attacker unstunnable, we could certainly make some team-stamped ones. And in reality, Battle of Wills is team-stamped to the “Willpower Team.” Plus, I liked the idea that the card would be weaker in the context of Sealed Deck and Draft, since opposing characters would be likely to have willpower.

As an aside, it’s worth pointing out that back then we were considering calling the Green Lantern team the GL Corps (or Green Lantern Corps).

Green Lantern Character

6 Cost

13 ATK / 11 DEF

Willpower 5

At the start of the combat phase, if you control characters with a total willpower greater than 20, you may gain control of the initiative.

This one was an early attempt at seeing how easy it would be to generate and/or sustain a ton of willpower and what sort of bonuses we could give out as a reward.

This kind of card illuminated an important point about willpower’s role in Sealed versus its role in Constructed. It’s a lot easier to achieve a ton of willpower in Constructed than it is in Sealed, so the reward we give out for doing so has to be proportional either in scope or relative value. There was a lot of concern that if we made willpower too good in Draft, it would explode in Constructed.

Emerald Enemies Character

5 Cost

5 ATK / 10 DEF

Cardname gets +5 ATK while attacking.

Exhaust a character you control >>> If Cardname is hidden, its controller moves it to his visible area. Otherwise, its controller moves it to his hidden area. Any player may use this power.

Here’s an example of a wacky, hidden area card. The idea here was that you had a stat-advanced attacker (effectively, it’s a 10 ATK / 10 DEF) but a low-ATK defender. The cool part is that its controller can try to hide it in the hidden area, but the other player can force it out of hiding.

While the card didn’t make it into later iterations of the GL file, it might be something we come back to in the future.

Anti-Matter Character

4 Cost

9 ATK / 4 DEF

Concealed

Whenever Cardname attacks, move it from your hidden area to your visible area.

Whenever Cardname stuns a character, KO that character.

Whenever Cardname becomes stunned, KO Cardname.

With this one, I was looking for a riff on the Concealed mechanic that would let you hide your fragile, low-DEF character in the hidden area until the time was right to strike. There were several problems with the card. One, moving the character to your visible area wouldn’t mean much if it was KO’d during its attack. However, if there was a good chance the character would survive the attack, then it was probably too powerful. Just imagine attacking and KO’ing a character on a turn where you don’t have initiative, and then on the next turn, when you do have the initiative, you attack and KO another character. Yeesh.

While the card ended up getting cut, its legacy became Dead-Eye.

Manhunters Character

3 Cost

No ATK or DEF in the file

Swarm 2 (When Cardname comes into play, you may pay 2 resource points. If you do, you may put a card named Cardname from your hand into your front row.)

Meet the original version of Manhunter Guardsman and Manhunter Soldier. Darwin had been working on a non-collectible game concept a while back that he’d shown me, and while its basic play pattern involved a player taking turns putting a single unit into play, some units had “swarm,” which meant you could play more than one of them. It got me thinking on how that mechanic would fit into the Vs. System, so I tried it out with the Manhunters.

Meet the original version of Manhunter Guardsman and Manhunter Soldier. Darwin had been working on a non-collectible game concept a while back that he’d shown me, and while its basic play pattern involved a player taking turns putting a single unit into play, some units had “swarm,” which meant you could play more than one of them. It got me thinking on how that mechanic would fit into the Vs. System, so I tried it out with the Manhunters.

For a while, I’d been planning on doing tons of Manhunters with swarm, so I anticipated keywording it. However, it turned out the mechanic was not as deep as I’d hoped, and in the end, it was relegated to the 3-drop brothers.

Manhunter Ongoing Plot Twist

As an additional cost to play Cardname, exhaust four Manhunter characters you control. Ongoing: Characters your opponents control cannot recover during the recovery phase.

One of the goals of the Green Lantern set was to push off-curve strategies. I figured that we often have plot twists that require a player to exhaust a character, but what if we had some that required a player to exhaust several characters to get a dramatic effect. (Get Him My Petsss was always one of my favorite cards—and not just because of its name!)

The above card was one of the initial concepts I wanted to try out in GL. I originally had it as a Manhunter card, since I felt their Army nature would make them more likely to go off-curve. However, since we wanted to push off-curve strategies in all the teams, we decided to turn the mechanic into a cycle of four cards: Reciting the Oath, In Darkest Night, Anti-Matter Universe, and Council of Power. This also meant we could shift the above power over into the Emerald Enemies, where it made more sense.

Okay, that’s all I’ve got on initial design and development. Next time, I’ll talk about some more detailed design stories, including how we organized the teams and how we created the legacy characters.

Q&A

Today’s first question is something I’ve talked about a fair bit and something I touched on at the live chat on VsRealms, but I feel it’s worth bringing up one more time.

Hey Danny,

I was wondering if at any point you guys thought of doing a new "base" set, retouching all the legacy content, like a Secret Wars or Infinity Gauntlet (I am sure DC has something like that as well) set, which could be a larger set, similar in design to the Origins, and include older teams and add more personalities to them. Releasing a larger set would allow for much more diversity in the Modern Age types of tournaments.

Also, have you thought about any of the crossover material? I know DC and Marvel have done many crossover collaborations, so I was wondering if you guys had any thoughts on doing a crossover set, or if you were planning on leaving that for the players to do by mixing and matching teams.

Thanks,

Tom

Okay, I guess there are actually two questions here. The heart of the first one is how we feel about creating entire sets filled with legacy content without introducing new teams. There are actually several ways to do this:

1. We could release a set with no new teams and tons of legacy content for every major (and minor?) team we’ve ever done. The set would be pretty awkward for Sealed or Draft, and it wouldn’t necessarily have a whole lot of mechanical coherence, but it would cover a lot of ground toward giving old teams new stuff.

2. We could make a set that included the usual breakdown of major and legacy teams, but each of the major teams would actually be an older team. For example, we could make a Batman/Superman set where the four main teams were the Gotham Knights, Arkham Inmates, Team Superman, and Revenge Squad. Each main team would receive a ton of new content, and the legacy teams would get their usual handful of cards.

3. We could make a set that re-featured a couple of teams while introducing a couple of new ones. For example, perhaps we could do a DC Space set that brought back the Green Lanterns and Anti-Matter teams and added the Legion of Superheroes.

I’m interested in hearing which of the above methods (if any) you guys would be most excited about.

As far as a crossover set, I can tell you that the guys at the office would love to do one. It’s mostly a question of getting Marvel and DC to okay it.

This next question is an excerpt from one of Rui’s super-long many-question-containing emails.

On the IP Research, I think it would be interesting to know what sites you guys used. This is especially because it might help fans find info about those cool details (like your buddy Rot Lop Fan, who, until you explained the story, we just called "Squid").

—Rui

Here are some of the links we use when digging for character info. (This is just me going through a bunch of my bookmarks.)

http://www.dcuguide.com/Who_Home.php (The DC Who’s Who Page)

http://fastbak.tripod.com/ (The New Gods Library)

http://www.titanstower.com/index.html (Tons of Teen Titans Info)

http://www.geocities.com/TheTropics/1185/jfiles/superman_connect.html (Super Stuff on Superman)

http://members.aol.com/doomscribe/faq.htm#8 (Dr. Doom FAQ)

http://www.fantastic4.net/ (Info on the FF)

http://www.samruby.com/villtoc.htm (Sinister Syndicate Stuff)

http://www.chronologyproject.com/ (Marvel Chronology project)

http://www.faqs.org/faqs/comics/xbooks/where/part2/section-3.html (X-Men Resources)

http://www.spiderfan.org/ (Spider-Man stuff)

http://www.avengersforever.org/characters/characters.asp (Avengers Profiles)

That’s it for questions today. Actually, this seems like a good time to point out that the past couple of weeks have been super-busy for me, mostly because on top of my usual workload, I needed to prepare for the live chat on VsRealms and answer all the questions they didn’t get to. Also, it seems like everyone I know was born in June, because the last couple of weekends have felt like wall-to-wall birthday celebrations, which is seriously cutting into my “free” work time.

My point is, I seem to have fallen way behind on answering emails sent to my metagame account. So to anyone who’s sent me an email in the last few weeks, I’ll be getting back to you soon.

Send questions or comments to dmandel@metagame.com.

And tune in next week for more hot design bible action!