Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Alright, guys, this is it. The final countdown. The end of the road. The article that ties all of the things I’ve been trying to help you learn into one coherent strategy. Hopefully, you have taken it upon yourselves to draft as much as possible in the last week to try to get the finer points from these articles down. It’s not easy, but with a little work and perseverance, you can do it.

5. General Strategy...........................................................................29

When Does My Deck Want To Kill?................................................29

Building My Deck.......................................................................30

Hidden Gems............................................................................35

This week will tie all of the other points together and help to develop some strategies that are necessary to master in order to succeed at Vs. System as a whole, not just in Sealed Pack. I guess the best place to start is the beginning of the section, so let’s dive on in.

“After your deck has been constructed, there are a few questions you will have to ask yourself in order to optimize your chances of winning. The first and most important question is how quickly your deck can kill.

“The answer to this question is highly dependant on the format in which you are playing. In Green Lantern Corps, for example, a deck could very easily play a large number of characters with huge DEF. This forces the game to go longer because more attacks must be made to break through the wall that those large characters create. If your deck is adequately equipped to deal with the large characters, it would be feasible to say that your deck is capable of killing on turn 7. However, if your deck is ill equipped to deal with the larger characters, you might not be able to kill your opponent until turn 8 or even 9.

“The reason this is so important is that it has much bearing on which initiative to choose. It would be fair to say that many games are won, whether inadvertently or not, by the roll of the die. Most often, it’s due to a player’s unfamiliarity with this cardinal rule: you want the initiative on the turn in which you want to kill your opponent. As has been explained previously in this manual, you cause the most endurance loss to your opponent on the turns in which you control the initiative. This is because attackers deal breakthrough. Defenders get to deal some endurance loss by stunning attackers, but it doesn’t compare to the amount of breakthrough endurance loss done in a game.

“Since it is clearly to your advantage to have the initiative whenever you can get it, you should always strive to get the initiative on what you would like to be the final turn of the game. As the game progresses, the relative size of the characters goes up sharply. Larger characters deal more breakthrough endurance loss. Having initiative on the last turn of the game means that your large characters are the ones who deal that endurance loss.”

This concept took me way too long to grasp. I’m not dumb; this was just on a level far higher than I was used to thinking about this game. Attacks I could do. Formation? Yeah, it’s a little harder, but nothing I can’t handle. But this was thinking way ahead of the game. It’s really amazing how many games I’ve seen lost because one person picked the wrong initiative for no reason other than that he or she didn’t know that the other one was needed.

This is just one of the many concepts that the better players in the game know by heart, even if they don’t know they know it. It just makes sense to them. After a bit of thought and much explaining, it makes sense to me, too. After all, if most games end on turn 7, why wouldn’t you want to be the one attacking on that turn?

Getting a good feel for the tempo of a set takes a while, though. For example, in Green Lantern Corps, the group I play with frequently saw our games going to turn 9 (and even 10 from time to time). As we got more accustomed to the set, though, games were shortened tremendously. We were reliably able to kill on turns 7 and 8. This has a few different effects on the format. First off, it makes certain cards much worse. For example, Ganthet was initially a tremendously powerful card. With games going to turn 9 or 10, he had multiple turns to gain endurance. However, when the games got shortened by about two turns, he became a weak 7-drop. The games had become much more aggressive, so he wasn’t able to stay around long enough to make a difference. He also didn’t have all that much impact on the turn he came into play, so he was just inferior to other options.

Getting a good feel for the tempo of a set takes a while, though. For example, in Green Lantern Corps, the group I play with frequently saw our games going to turn 9 (and even 10 from time to time). As we got more accustomed to the set, though, games were shortened tremendously. We were reliably able to kill on turns 7 and 8. This has a few different effects on the format. First off, it makes certain cards much worse. For example, Ganthet was initially a tremendously powerful card. With games going to turn 9 or 10, he had multiple turns to gain endurance. However, when the games got shortened by about two turns, he became a weak 7-drop. The games had become much more aggressive, so he wasn’t able to stay around long enough to make a difference. He also didn’t have all that much impact on the turn he came into play, so he was just inferior to other options.

We now return you to your regularly scheduled program.

“In Sealed Pack, the decisions you make while drafting are only slightly more important than the final decisions you make while building your deck. It’s important to make sure that your deck has the correct ratio of plot twists to characters and the correct curve. It should also follow a coherent strategy into which all of the cards fit. Finally, it should have an ample amount of things to do on both players’ initiatives.

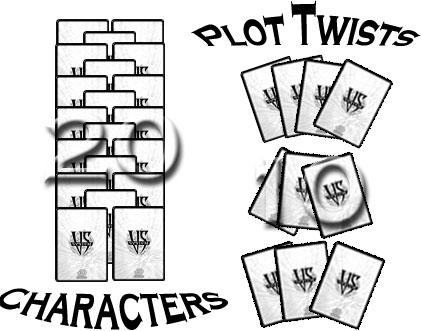

“Earlier, it was mentioned that you ultimately want around ten to twelve plot twists and twenty or so characters to round out your deck. This is for maximum consistency in your draws. This mix assures that you’ll draw the proper number of plot twists while leaving room in your deck for the proper number of characters with which to assemble your picture-perfect curve.”

As I said before, his curve is a little outdated, so I’ll just re-post it here for reference. The optimal curve is one to two 1-drops, two to three 2-drops, four to five 3-drops, four to five 4-drops, three to four 5-drops, two to three 6-drops, and one to two 7-drops. If you need an explanation of this curve, check out the last installment of the Manual.

“By the time you build your deck, you should already have a pretty good idea of how your deck wins. You should know its tempo and general style of play. If you are a little unclear, or if that information changed mid-draft, you should check it over again now. Is your deck an aggressive one that wants to end the game quickly? Does it use more of a controlling strategy in an attempt to draw the game out? These are very important when deciding what to include in the final version of the deck.

“Your deck’s identity will determine the final selection of cards that make it in. If your deck follows a more aggressive strategy, you would choose to include that Guy Gardner, Strong Arm of the Corps in your deck over that Katma Tui. Also, your plot twists would be of a more aggressive slant. You would gear more toward ATK-raising plot twists than those that raise DEF. Your final card selection should have as much synergy as possible. Understand what your deck wants to do and your decisions become much easier.”

In the final part of this section, the author tries to explain another of those higher level strategies. However, it’s a little difficult to understand it the way he puts it, so I’ll paraphrase for the sake of making it, well, understandable.

He talks a great deal about having things to do on both players’ initiatives. During your initiative, it should be fairly apparent what you have to do. You attack. Lots. However, on your opponent’s initiative, it’s a little less clear what needs to be done. The simplest thing to do is make your opponent’s decisions as difficult as possible through the clever use of plot twists or character abilities. Good defensive plot twists such as Pest Control or Helping Hand are good examples. However, you could also play cards like Nasty Surprise or Blown to Pieces to make sure your opponent’s attackers stun. As long as it’s something he or she didn’t plan on while attacking, it’s useful.

The main reason you don’t want to remain passive on your opponent’s initiative is that all of the decisions become straightforward if you do. It becomes chess instead of poker. If you have no extra information you’re hiding from your opponent, there’s no fear. Fear is an important tool in this game. When your opponents don’t know what you have in store for them, they make mistakes. This is exactly the type of situation you’re trying to create. You want your opponent to misplay his or her turn. Encourage this by making the opponent’s decisions as difficult as possible.

“During the course of drafting a particular set, the values of certain cards will fluctuate. It’s important to keep an eye out for cards that escalate in value as the format progresses. These hidden gems often slip through the cracks at first, mostly due to inexperience with the format. However, as time goes on, the format begins to settle down a bit and you get a better grasp of its nuances. G’Nort is a perfect example of one of these gems.

“During the course of drafting a particular set, the values of certain cards will fluctuate. It’s important to keep an eye out for cards that escalate in value as the format progresses. These hidden gems often slip through the cracks at first, mostly due to inexperience with the format. However, as time goes on, the format begins to settle down a bit and you get a better grasp of its nuances. G’Nort is a perfect example of one of these gems.

“On his own, G’Nort is a relatively solid character. He is mildly important to a good deck because he fills the necessary 1-drop portion of the curve. However, as the format progressed, a change took place. The off-curve Green Lantern decks proved their worth in Sealed Pack play. In these decks, G’Nort was essential. He was arguably the best character in the deck. He went from being a card that would make the deck if drafted to being a first pick. All of this happened because the format had a chance to settle down so that players could get a grip on it.”

That’s going to do it for this week, guys. I hope you’ve enjoyed everything so far. Next week will be a little more hands-on. His final FAQ section is a bit outdated, and I wanted to spruce things up a bit. I want to get as many questions from all of you as I can and then answer them all in an FAQ of my own. I’ve already had some very good questions emailed to me that I guarantee will be posted next week, but I’d really like more. If you have any questions at all about Sealed Pack play, card evaluation, or anything like that, please ask me at the_priceis_right@yahoo.com. I’m looking forward to your questions and I’ll do my best to answer them next week.