|

The Sentry™

Card# MTU-017

While his stats aren’t much bigger than those of the average 7-drop, Sentry’s “Pay ATK” power can drastically hinder an opponent’s attacking options in the late game.

Click here for more

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Deck Building 101 Deck Building 101

Today I want to talk a little bit about deck construction. Not so much about the details, like how many characters you should put into your deck or what complement of plot twists to use, but about some general thoughts you might want to consider. First, I’ll talk about sticking to your game plan, then I’ll go over enforcing your will on the game, then I’ll take a look at how the initiative can influence your deck, and I’ll finish up with Dr. Doom riding a surf board.

Part 1: Stick to the Plan

There are many approaches you can take when you sit down to design a deck. Maybe you want to build a X-Men deck. You don’t really care too much about if or how you’re going to win, you really just want to play all your favorite characters. Maybe you want to build a wacky theme deck like all Random Punks and Mojo, or something with a weird goal, like teaming up the Sentinels with Dr. Doom so that you can use Underground Sentinel Base to start spitting out Tibetan Monks. Or maybe you want to crack some heads with that cutthroat Skrull–Negative Zone deck that’s been dominating the tournament scene.

Whatever kind of deck you want to build, you need to decide what your game plan is going to be. And for the purposes of this article, by "game plan," I mean how you’re going to try to win the game. (Yes, if your goal is to create the Tibetan Monk Factory, you’re going to need a game plan too, but for now I’m going to stick to the basics.)

Every card you put in your deck should actively contribute to your winning the game. This may seem like a no-brainer. You’re not going to put cards into your deck that will make you lose, right? Let’s look an example. You’re building a Brotherhood Rush deck with aggressive resources like The New Brotherhood, Savage Land, and Asteroid M. You’re happy with your character layout, and you’ve got a nice spread of plot twists like Flying Kick, Savage Beatdown, and The Mutant Menace. You’re down to the last few slots in your deck, and you’re trying to decide between Finishing Move, Avalon Space Station, and Nasty Surprise.

In a vacuum, all three of these cards are strong. KO'ing a stunned character seems good, but so does bringing your own characters back from the KO’d pile, and so does taking down a large incoming attacker. So which card makes the cut? Well, you could just run them all and have a 68-card deck, but that’s probably not a good idea. (If you’re not sure why that’s not a good idea, let me know, and I’ll go over it another article.)

The answer to which card you should pick is intimately tied into your game plan. This is supposed to be an aggressive smash 'em up deck. If things are going well, you should be taking down your opponent’s characters left and right, Ko'ing without the help of a Finishing Move (and if things are going poorly, a Finishing Move probably won’t save you). Plus, you’ll probably want to use your characters to attack and attack and attack—it could be wasteful to have to exhaust one of them to play the Move. Of course, this is not to say that Finishing Move is bad, just that there might be a better option for your deck.

Which brings us to Avalon Space Station and its built-in card advantage. It lets you trade one card in hand for two cards in hand, over and over. What a deal! The most obvious use for this card is to power up a couple of your characters, than return the discarded cards to your hand to power them up again. Combine it with Lost City for some serious smashing. And maybe we should make sure our character suite includes multiple versions of the same characters to increase the likelihood that we’ll be able to power-up. And . . . BAM! Suddenly we’ve lost focus. We’re now designing a different deck. Not a worse deck per se, but a different deck.

I think the correct call in the above example is Nasty Surprise. A Brotherhood rush deck has lots of offensive tools for when you have the initiative. But when you’re on D, there isn’t a whole lot going on. Nasty Surprise not only increases the chances that your opponent will lose a character even when he or she has the initiative, but it also causes some more endurance loss—always a good thing in this type of deck.

The point you should take from all this is that it’s often a mistake to judge in a vacuum one card’s value relative to another’s. In and of itself, Avalon Space Station seems more overtly powerful than Nasty Surprise, in that the Station lets you generate lots of extra cards, while all the Surprise does it take down an attacker. In fact, the Station is powerful enough that you might want to build an entire deck around it, but just because it’s a good card doesn’t mean it goes in every Brotherhood deck.

Rule #1: Understand your game plan and choose cards accordingly.

Part 2: Know Your Enemy

An average game of Marvel can be divided into the early, middle and late game.

The first couple of turns constitute the early game, with each player placing some resources, recruiting a couple of characters, chipping away a bit at each other’s endurance, and perhaps setting up a bit for later turns with cards like Cerebro or Doom’s Throne Room. Barring a Finishing Move, characters are pretty safe in the early game because of the free recovery each player gets.

The middle game is usually around turns 3–5. Here, larger characters start hitting the table, ready to take larger, more relevant bites out of players’ endurance totals. The meat of the game is in the middle turns, when there are lots of characters in play, and each player is jockeying for board control leading up to the endgame.

Turns 6–8 are the late game. Huge, board-sweeping effects and super-charged finishers hit play, and being at 25 endurance doesn’t feel so safe anymore. The late game is, well, when the game ends.

But like I said, that's how an average game of Marvel breaks down. You might be playing the Brotherhood rush deck that wants to win on turn 5 every game. For that deck, your early game might be turn 1, the middle game turns 2–3, and your late game is trying to ram home enough damage on turns 4 and 5 before your opponent starts dropping bigger characters to swing the advantage back.

Conversely, you might be playing a Fantastic Four combo deck, where the early game is dropping some annoying defensive characters like Invisible Woman or Medusa while searching out “free” equipment with Mr. Fantastic and Baxter Building, the middle game is filling up your board with high-defense characters further bolstered by Unstable Molecules, and the late game is attacking with your large team of fully-equipped characters. In this deck’s case, the early, middle and late game are fluid—basically contingent more on how long it takes you to set up than what turn it is.

What makes things interesting is that each player has his or her own ideas on what the early, middle, and late game should be. Let’s say the two above decks faced off. The Brotherhood deck wants to game to end quickly, finishing off the FF deck before it can set up. All the FF deck wants to do is survive, knowing that if it gets a chance to drop its 6 and 7 cost characters, it will likely swing the game. I like to think of this as each player trying to enforce his or her will on the game. This was an extreme example, rush versus stall, with obvious implications, but it gets even more challenging when you’re playing a more middle-of-the-road deck.

Let’s compare a standard X-Men beatdown deck to the two above decks. The X-Men deck wants to recruit excellent characters, support them with cards like Danger Room and Children of the Atom, and win through quality attacks. It doesn’t have the blistering speed of the Brotherhood deck, and it doesn’t have the explosive potential of the FF’s equipment craziness, but it’s consistent, reliable, and resilient. Let’s look at its matchups. Against the Brotherhood deck, the X-Men player wants to play lots of defense, protecting his or her endurance total and characters until he or she can drop monsters like Colossus or the berserker Wolverine. But against the FF deck, the X-Men player has to be aggressive, knowing that the FF deck also has high cost monsters that will trump his or her own when backed up by equipment.

When you sit down to build a deck, it’s important to stick to your game plan, but it’s also important to understand how your opponent’s game plan may alter yours. A lot of this is tied into the metagame (the other possible or popular decks in the environment).

Rule # 2: Understand how your deck’s game plan changes based on different matchups.

Part Three: Show Some Initiative

The Marvel TCG uses an initiative system. Basically, the players move together through each turn. In a two-player game, the player who has the initiative is pretty much on offense, while the other player is on defense. One thing you’ll learn quickly is that a deck can play out very differently depending on who starts the game with the initiative. This is important in deck construction for two reasons. One, you should decide if you want to start with the initiative or not (assuming you won the die roll and got to decide), and two, you should be prepared to run your deck well even if you are not happy about who started with the initiative.

There are lots of factors in deck design when considering the initiative, enough that I’ll probably go over some of them in detail at a later date, but for now try to keep in mind this simple fact:

A player will win the game on a turn when he or she has the initiative.

This may not always technically be true, in that you may actually reduce your opponent’s endurance to 0 on the very next turn. But nine times out of ten, a player will win the game outright or at least decide the eventual outcome of the game on a turn when he or she has the initiative.

What this means is that while playing, you should always be thinking about what’s going to happen when the initiative moves to the next player, whether you’re about to be on offense or defense. What it means for deck construction is that you should take into account what the key decision turns (that will decide if you’ll win the game) of your deck are.

Rule #3: Understand how your deck will play differently if you start with the initiative or without it.

Part Four: Cosmic Thing

Somtimes you want to be an evil, mystical, scientific, genius dictator, and sometimes you just want to surf.

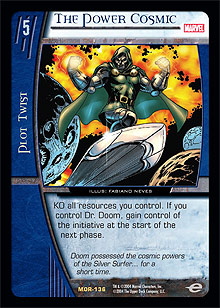

I just went over how important the initiative is both while building your deck and while playing. But for some decks, you just don’t care. Sure, The Power Cosmic has a hefty price tag, what with that whole "you don’t have any resources left, and if you don’t win the game this turn you’re going to be in a lot of trouble, so you better win this turn" thing. But man, what an effect! With a full set of The Power Cosmics and some ways to search for them like Boris or Doom’s Throne Room, you can virtually guarantee having the initiative on the turn you want it. Of course, just having the initiative doesn’t mean you’ll also have the tools to win the game. That’s up to you.

But just to throw out a little bit of a challenge, here’s something that happened during a playtest session a while back. One player, let’s call him “Gavin,” was playing a Sentinel swarm deck, while the other player, who we'll call “Omeed,” was playing a Doom control deck sporting The Power Cosmic and the Sub-Mariner.

Four Score and Three Endurance . . .

On turn seven things were going well for Gavin. He had about six Sentinels in play, including Master Mold and a bunch of Wild Sentinels, and more importantly, he had the initiative. Omeed was low on endurance and Gavin sensed victory. He placed his seventh resource and recruited a couple more Sentinels. Unsuspectingly, he left four of his Wild Sentinels in the support row where they were “protected.” Omeed’s board was Dr. Doom and one or two of his smaller minions. He placed his own seventh resource, dropped Sub-Mariner, and smiled.

“Are you ready for combat?” Gavin asked.

“Not yet.” Omeed said. And then he played The Power Cosmic.

Not only did Omeed steal the initiative, but he did it after his opponent had set himself up in an extremely dangerous position against the Sub-Mariner. Each of his support row Sentinels had just become a tasty snack for the 15/16 Flier (Subby readies whenever he attacks a support row character, allowing him to attack again . . . and again). To add insult to injury, Omeed played a couple of combat modifiers, and when the dust finally cleared, there were a lot of broken robots, and Gavin had lost 83 endurance.

Since then, there’s been a big “83” hanging above Omeed’s deck, sort of a thrown gauntlet daring anyone to try to cause that much carnage in a single turn.

Rule #4: Stealing the initiative = Good.

Okay, that’s all for today. Just a reminder: Please send any rules questions you have to danielcmandel@yahoo.com.

Tune in on Monday for a look at stretching your mind.

|

| |

| Top of Page |

|

|

|

|

|