Last week I looked at the researcher’s work on set design in terms of fixing rosters and naming cards, with specific regard to the Justice League of America set. But even when the roster is all but finalized, and the vast majority of the card names are set, there is another important step to be done: the art requests.

The Pen is Mightier than the Card!

First off, just what is an art request? Simply put, it is a description, approximately one paragraph in length (anywhere from 15 to 75 words), of what the art for a card will look like. In other words, this is the design of the card art, which is then sent to an artist, who will re-interpret the words and turn them into the piece of art you see when you bust open those packs at the sneak previews. The paragraph is similar to those you may have seen in Ben Seck’s Fan Card Crossover series, except that it’s somewhat limited to the image description without the “setting” and “mood” details—though they may well decide to incorporate those into future sets’ art requests.

Now, I would never presume to take any credit away from the brilliant job the art department does, nor from the amazing artists that we are fortunate enough to have painting pretty pictures for our game. (I still can’t believe George Perez even looked at something I wrote before he picked up his pencils.) We merely provide the setting, so to speak, for them to unleash their talents. Also, the artist’s vision may not match the writer’s, so what hits us when we are writing our art requests may turn out completely differently from how we envisioned it—though sometimes the art is exactly as we imagined it to be.

The art request process varies from person to person. For me, there is no straight line that I take when writing requests—I brainstorm ideas, write them out, clean them up, then restart the process. Some people like to get all of their ideas out first, then write up all of the requests at once, but not me; I like to do them as I come up with the ideas—and that also gives me a chance to send portions of the requests to the lead designer. That way he can critique the requests and set me on the right track so that my vision for the artwork matches his vision for the set as much as possible.

The art request process has changed somewhat since I worked on the JLA and X-Men sets. For those sets, I wrote just about every art request in the set, and the vast majority of them were used for the final cards. More recently, just as the research team has grown larger, so has the team for art requests. For the Legion of Super-Heroes set, for which we recently completed the art requests, several researchers were assigned a portion of the art requests, then, upon completion, another batch. This is a good idea, as it allows the lead designer to replace a researcher if his or her creative style doesn’t fit that of the set, without losing as much work. It also gives a wider variety of styles within a set, which keeps the art fresher and more interesting. And it allows for some overlap in the requests so that they have more choice in terms of final images.

In addition, while I wrote the art requests for the vast majority of the cards in the JLA set, that doesn’t mean that they were all used. Cards change, new cards are added at the last minute, previously requested images are often pulled from the vault and used—and sometimes the lead designer (or somebody else on the team) comes up with an idea that is really cool and that ends up being used instead. For example, Matt Hyra came up with the idea for Criminal Mastermind in the JLA set—an amazing image of The Atom caught in a fiendish trap laid by Chronos! The art request originally submitted for this card was not one of the better image ideas in the set (sometimes ideas simply dry up, and one is forced to resort to stock image ideas). Imagine if the card had been this instead:

In addition, while I wrote the art requests for the vast majority of the cards in the JLA set, that doesn’t mean that they were all used. Cards change, new cards are added at the last minute, previously requested images are often pulled from the vault and used—and sometimes the lead designer (or somebody else on the team) comes up with an idea that is really cool and that ends up being used instead. For example, Matt Hyra came up with the idea for Criminal Mastermind in the JLA set—an amazing image of The Atom caught in a fiendish trap laid by Chronos! The art request originally submitted for this card was not one of the better image ideas in the set (sometimes ideas simply dry up, and one is forced to resort to stock image ideas). Imagine if the card had been this instead:

“Lex Luthor in the foreground, his hands steepled over his chin, with Prometheus and the General in attack poses behind him. (See the cover of JLA #36 for reference.)”

One source for our image ideas is the comics themselves—and several images will be taken from key moments in comics history. A great example of this is Crisis on Infinite Earths, which has the absolutely classic image of Superman crying over a dead Kara Zor-El. Phil Noto did a superb job of translating the classic Perez cover of Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 onto the card. However, occasionally, when stuck for an idea, we rely on previously drawn images a little too heavily—and Matt caught this one and had a far better idea for it.

This is the reason why creative minds are needed for this kind of job. For one, we have no clue which artists will be working on the cards, so we have no style to consider while dreaming up our art ideas. Plus, we have no contact with any of the artists, so we also have no access into their minds—we can only guess at how our design ideas will be interpreted by their brushes. We need to be able to come up with a couple of hundred ideas that are not redundant or repetitive, and that stylistically and thematically fall into place together. This is something that comes with experience—and, admittedly, it also becomes easier to think in terms of card art after having written a few hundred requests.

The Rules of Engagement

When a set is in the throes of design, the entire team—R&D, researchers, and so on—has to come up with ideas for far more cards than will actually be used. I mentioned that sometimes older card images are used in new sets—this is because Upper Deck requests images for more cards than they will use, and sometimes, when we come up with multiple ideas for artwork, they will request all of them and choose the most appealing one. Sometimes, as well, the additional art turns up in other forms—like alternate art cards or alternate foils. You may have noticed that a couple of cards in the X-Men set were more in the style of the Marvel Origins set—Rachel Summers, for example. This is because those were art requests for the earlier set that were not used until now.

The main benefit of having so many cards to work with is the amount of leeway it provides. Not all of a requester’s ideas will be good ones, so having a lot of extras leaves room to shove those less interesting ideas aside for better ones. Sometimes a request for card X will actually be used on an entirely different card. The main drawback is that the more ideas a researcher has to come up with, the harder it is to stay fresh. This is when we put our research to good use. One of the toughest parts of art requests is avoiding the mundane. However, we can’t get too creative, because there are certain rules to maintain. The most important of those rules are:

1) We are working with images that have to fit on a Vs. card, so they can’t be too busy or too intricate. We have to ensure that the players will be able to tell what is going on, and won’t have to work too hard to appreciate the cards. That doesn’t mean we can’t throw in Easter eggs (little hidden references or objects on cards),* or have some amusing or interesting background detail on the cards, but we need to avoid overloading the images as much as possible.

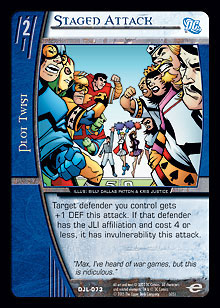

For example, Staged Attack is a very busy card that works. Here is the original request for it:

For example, Staged Attack is a very busy card that works. Here is the original request for it:

“On a football field, Maxwell Lord in the center, in a referee's uniform, with a whistle in his mouth; on the right side, lining up in football uniforms, are the Royal Flush Gang; on the left side, also in football uniforms, is Booster Gold (in the center of the line, slightly forward), flanked by Blue Beetle and Mister Miracle on one side, Martian Manhunter and Captain Marvel on the other. In the background, behind Maxwell, are Black Canary and Power Girl, with cheerleader's skirts and pom-poms.”

At that point the Royal Flush Gang was going to have a little more presence in the set, and, with that in mind, this image hits almost all of the necessary points: it’s got diversity of characters; thematic flavor (both in terms of the humor of the JLI comic and of a specific storyline—when Max Lord staged a Royal Flush attack in order to get Booster Gold into the Justice League, from Justice League #4); and an image that is certainly far from mundane. It’s busy because it has to fit a lot of content into a single card, including several characters (who have to be recognizable) and the idea of a football game (or else it would just look like a bunch of heroes and villains facing off, and would lose the creativity of the “staged” attack). The art was done by Billy Dallas Patton and Kris Justice, and they hit the nail dead-on: the 50-yard line, referee pinstripes, cap and whistle, and the cheerleaders’ pom-poms make the game aspect clear, and each costume is apparent enough so that the only character who is not entirely obvious is Max Lord—and those who recognize the “players” and the reference are likely to guess at his identity, as well.

An example of an image that is too busy is this original request for The Joker, Headline Stealer:

“Character Image. At a street-side newsstand, we are zoomed in on a hanging newspaper taking up most of the frame, on which is a picture of the Joker, in top hat and tails and with a monocle in his right eye—front page news in the Gotham daily, a picture of him bowing, his head raised and facing us with his exaggerated grin, taking up most of the paper's front page. The picture is a 3-D Joker, taking up most of the front page of the newspaper bowing right out of the newspaper, and in full color, as opposed to glimpses of other newspapers with B&W, 2-D pictures.”

This would have been an extraordinarily cool image, but the art department felt it was too difficult to pull off on a Vs. card. They replaced it with the current image, which hits the aesthetic flavor of the card perfectly: The Joker gleefully reading about his exploits, which have made front-page news.

2) It is imperative that character cards focus on the character. This may sound like a “duh” declaration, but it’s not as obvious as one may think. Sometimes we get cool ideas, or get carried away, and the focus isn’t as centered on the character as it should be. Keep in mind that there are several ways around this—one can come up with ways to keep the focus entirely on the character without the character even being in the image—but the focus should always be on that character. The best example of this is one of my all-time favorite Vs. images,** which is currently my desktop image (with many thanks to Matt, who provided me with a shiny jpg). It is the image of Scarecrow, Psycho Psychologist, which is so masterfully done by John Van Fleet that I could not imagine even a single thing about it that could be improved.

“Character Image. Scarecrow's laughing face, seen reflected in the polished metal of his scythe. Behind the scythe, we see a figure, tied up, on a psychologist's couch.”

The image was a simple and straightforward one—someone being held hostage by the Scarecrow, as the villain enjoys the anguish and fear he is creating. Van Fleet took it one step further and instilled the victim with terror, which creates a sense of tension in the card that ups the ante by a ton. You’ll notice the term “character image” in the request as well—this is a signifier that tells the artist that the request should focus primarily on the character, so that they don’t get carried away with the image. In this case, Scarecrow doesn’t actually appear in the image—only the reflection of his face does—and yet he is very present, in the tension and fear alone if nothing else. He is very much the focus of this card.

On the flip side, here is the backup image idea put forth for . At that point, his version was “Aloof”—a placeholder version name to give the art requester an idea of the kind of image the lead designer wanted. If Batman’s version (Avatar of Justice) had been finalized, the art requests may have been very different, and the card may not have looked as it does (which is a very interesting interpretation by Chris Bachalo of a fairly basic request).

On the flip side, here is the backup image idea put forth for . At that point, his version was “Aloof”—a placeholder version name to give the art requester an idea of the kind of image the lead designer wanted. If Batman’s version (Avatar of Justice) had been finalized, the art requests may have been very different, and the card may not have looked as it does (which is a very interesting interpretation by Chris Bachalo of a fairly basic request).

“Character Image. Batman, on a cliff top, in the center of the frame, cracking his knuckles, staring straight at us as though we were his intended target. Behind him, on either side and obscured by his cape and body so that we can only make out their face and one arm, are Green Arrow pointing an arrow at us, and Steel, who is slapping his hammer’s haft against his palm. They should all have a no-nonsense, ‘don’t mess with us’ look on their faces.”

This request didn’t make the cut because, to be honest, it’s not a very good character request. While having other characters in a character image can be a good thing, especially in combat scenes—or amusing images like that of Maxima—this image simply doesn’t focus on Batman enough. Even though he is central to the image, there is nothing about the image, as a whole, that screams “Batman” to me. It would probably make a decent plot twist image, though.

The Creative Process

Now you know what an art request is, and the ground rules for how a request should be done. Here is a look at the process itself.

At the point in time that we do the art requests, if we are fortunate enough to have been on the research team (as was the case for the JLA set), then part of the work has been done already. As I do the research for a set, I’m also constantly on the lookout for image ideas and will jot them down whenever I come up with something. I may be on the bus or in the shower when something comes to me, and I’ll jot it down as soon as I am physically able. I also keep scrap paper and a pen by my bed, as I often come up with ideas upon waking or just before sleep, and don’t like to have to rouse myself to get up to grab the necessary implements to write it all down.

For the Legion set, however, I wasn’t on the research team, and that meant that I had to do a fair amount of research before setting down the art requests. Sure, I know a ton about comics—huge collection, and fanboy obsessiveness—but that’s really not enough. For one, each set has its own theme, and various storylines that are integral to the set’s overall themes. Yes, the Green Lantern Corps set was about the various Green Lanterns and their enemies, but you can trace specific storylines throughout the cards—and a good deal of one’s ability to trace these storylines comes from the art. As well, it is always a good idea to refresh one’s memory—there are all sorts of details in the comics that are easily forgotten when you read as many comics on a regular basis as I do. Seeing one single panel in a comic you haven’t read in years can drive a half-dozen ideas into your skull.

One advantage we have is the spoiler. With the wonderful world of nondisclosure agreements, we often have access to early versions of the spoilers, which not only indicate what cards to request art for, but also provide a handle on where the set is going thematically. However, we cannot count on the spoiler to guide us too much, as it changes drastically on a regular basis. The first JLA spoiler I got, on January 6, 2005, had several keywords that don’t exist in the game (and may never exist); a bunch of card names and versions that were still placeholders, or would be changed; and effects that would either shift dramatically or would be shunted to another card. I couldn’t count on Elongated Man having effect X when designing art for him, because he may well end up trading effects with Metamorpho within a week of my writing that request. So, while we can use the spoiler as a guideline, I was receiving a new version of the spoiler every week—sometimes more than one per week—so I simply could not rely on the spoiler too much.

With the research done and the ideas starting to blossom, the next step is brainstorming. I like to brainstorm for ideas by simply writing out as many image ideas as I can think of in a set amount of time, from both comic continuity and from my own head, and then trimming the fat and keeping the best. Some ideas I already had down, like the idea for Midnight Cravings, as seen in last week’s article. At that point it was called “Midnight Snack,” and it was one of the first requests I wrote down.

“Martian Manhunter seated at the JLI Embassy kitchen table, a plate of Oreos and a glass of frothy milk on the table. He has a milk mustache and is raising a couple of Oreos to his already chewing mouth, while he peruses a magazine (some funny magazine-parody).”

This idea immediately came to mind when the card idea was put forth. The early stages of brainstorming tend to reflect card names already accepted—coming up with ideas for names and ideas for images often go hand-in-hand—which is another advantage to working on the research for a set in addition to its art requests. Once the basic brainstorming is done, it’s time to sit down and write out the ideas into clear paragraphs. Since I am a writer by trade—not just for Vs. sites, or as a journalist, but also by degree (I’m currently completing a Master’s in creative writing)—I tend to frame the requests in a fairly consistent writing style. I’ve also studied a lot of films and screenplays, as well as drama and photography. This helps me to focus and visualize when I’m writing out the requests, which often use film and photo terms such as “frame” and “close-up.” I will also refer to “off-camera” events, as there can be information outside of our view that affects what we see. These terms are all common to screenplays. I tend to refer to “we,” another frequently used screenwriting term, framing the request from the point-of-view of the audience. It’s easier for someone to visualize your ideas if you explain to them what they are supposed to be visualizing.

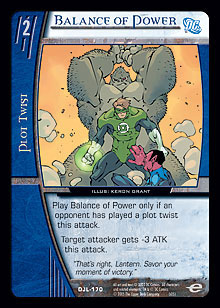

Once the ideas are written down, I brainstorm again. I also read a lot of comics while I’m doing the work. The requests tend to take a couple of weeks (or more) to complete, and during that time I put all of my regular comic reading on hold and read and reread issues that include characters and teams I’m working on. Many of the issues I will skim over, concentrating on the art; I like to get an idea of how the characters pose in the comics—their body language, expressions, and so on. Sure, different artists have different styles, but there is a visible difference in the body languages of Batman and Superman, which is captured by each and every artist on a consistent basis throughout comic history. The way that the characters come off is important when featuring them in art—especially when it’s a non-character card. Character cards are most often just the character posing in a given setting or situation that reflects that character; Batman in the shadows, Green Arrow with his arrows, Flash in some form of speed-image, and the like. But when you have a card that is situational—like Balance of Power—you have to go beyond the simple character pose. Here’s the original request for Balance of Power:

“Green Lantern moving in for the 'kill' toward a battered Sinestro, who is on one knee. Behind an unsuspecting Green Lantern is Gorilla Grodd, about to strike with both arms.”

“Green Lantern moving in for the 'kill' toward a battered Sinestro, who is on one knee. Behind an unsuspecting Green Lantern is Gorilla Grodd, about to strike with both arms.”

Another simplified art request that doesn’t say much on the surface. But underneath it we see something about each character that is defining. Green Lantern is moving in for the “kill,” or knockout blow. This shows confidence, even arrogance, which is definitely a Lantern trait—especially for Hal. Sinestro is on one knee even though he’s “battered”—this shows an unwillingness to quit; Sinestro is proud and arrogant, and does not cave in easily. Grodd is about to strike with both arms—significant because it shows a position of strength, an animal-like way of attack, and a typical style of fighting for Grodd. Two sentences that say a lot more than one would think from the surface. And one has only to look at the name of the card and the great image by Keron Grant to see the body language translated into the image—while Sinestro’s raised hand perhaps paints him as a bit too afraid, the flavor text pulls it back together, and the little dust clouds add some fine background detail—all showing a lot of presence of mind on the part of the artist in evoking the idea in a flavorful way.

My file went back and forth between myself and Matt, with his commentary and suggestions being tacked on to every version of the file he returned to me; for example, reminding me not to put JLI characters on JLA cards. (Although characters may be on both teams in the comics, if they’re only on one team in the set, it becomes confusing to players to decipher the plot twists and locations if characters from both teams appear on a card—especially when the team names differ by only a single letter). He would remind me that a character without range shouldn’t be represented in her character image as holding a gun, and request that I add little details (things like costume changes, or the blurred S emblem on Ray Palmer ◊ The Atom), and whatnot. His ideas added flavor to the cards, and really helped me to flesh out my ideas more creatively. It is integral for any creative mind to be open to constructive criticism, and to be able to self-edit. I could not afford to get attached to my ideas; if the lead designer says to drop it in favor of another idea, it’s my job to do so. I could plead my case, and sometimes convincingly, but in the end he has the final say. I wouldn’t even know which requests were used until I saw the cards themselves, as some of my requests were replaced.

Matt also took a couple of basic request ideas and ran with them, vastly improving upon them. The best example of this is the alternate foil idea for Plastic Man. I had a lot of trouble coming up with ideas for Plastic Man. I knew he could form all sorts of shapes, but, to be honest, he was one of the characters I was least familiar with in the entire set. The primary idea I had for him was to have his body way in the background of the image with his head and arms stretched all the way to the front in a fairly extreme close-up. Hardly a genius idea. Then I thought of the idea of a portrait of his head, where his body would be the frame of the painting.

“Character Image. Plastic Man pretending to be a self-portrait 'painting' of his head and torso—with his body twisted into a fancy frame.”

This was not even half as cool as what Matt came up with—the “Plastic Man as a Vs. card” image is nothing short of brilliant. Which proves that being a part of any team, even if the majority of the project (as with art requests) falls upon a single person, means a joint effort among the entire team. The JLA set is one of the best sets in this game, and that is due to the large group of people who worked on it together. Art requests are no different—Matt’s feedback and ideas were as important to the process as my own research and ideas were.

After he received the final file, made the changes he needed and sent it off to DC for artist assignments, the hardest part began—the long wait until I could see for myself how it turned out! And I think, in the end, it turned out pretty well.

NEXT: A different side to researching for a set as the process begins anew for The X-Men set!

Questions? Comments? Send ’em along and I’ll try to get them answered in the column! Email me at Kergillian (at) hotmail (dot) com.

* In fact, I was instructed to create a certain number of Easter eggs in the art requests. While I won’t spoil them all, the most obvious one is on Funky’s Big Rat Code, which I mentioned last week. The code reads “Kergillian”—and for the record, that was not in the original request, which read:

“Funky Flashman writing an encoded note, with the code clearly seen in a book on the table next to him. Secret message should read: Be sure to play your Vs. (encoded and backwards). (For reference, see the letter column of Secret Society of Super-Villains #9 or http://www.geocities.com/dstepp.geo/Archives/FUNKYCODE.html.)”

Matt snuck my name in, and I didn’t even know until it was mentioned on my mailing list by one of my moderators! This goes to show that the R&D team members add their own touches to the cards at times. Which means that there are probably a bunch more that I don’t even know about. . . .

** For the record, my favorite art request that didn’t make it into the set was this request for Killer Frost:

“Character Image. Killer Frost, in her ice form and in the center of the frame, looking like a dainty Victorian lady, offering her hand to Firestorm. He is leaning forward, his lips touching the back of her hand. His hand, arm, and head are frozen solid in ice, though the rest of him hasn't frozen over yet—it should look as though the ice is creeping down his body, which is half off-screen.”

This is probably the only art request I got attached to that didn’t make it in. Hopefully they did make the image and I’ll get to see it someday. . . .

Also known by his screen name Kergillian, Ben Kalman has been involved in the Vs. community since Day One. He started the first major online community, the Vs. Listserv, through Yahoo! Groups, and it now boasts well over 1,850 members. For more on the Yahoo! group, go to http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Marvel_DC_TCG.