Normally, after I attend a big event like a $10K or a Pro Circuit, I write a tournament report about it. This article was supposed to be about my experiences at Pro Circuit Indianapolis 2006, including the decks I faced, the players I met, what I saw at the convention, and the fun I had while playing Vs. System. I began keeping notes at the start of the tournament, but halfway through Day 1 my record wasn’t looking so hot, and I was too depressed to continue jotting down how badly I was doing. Afterward, I ended up throwing out everything else I had recorded because a tournament report about not Day 2’ing isn’t very fun to write or interesting to read. I could have kept notes on the $10K that happened on Saturday, but at that point I had pretty much given up on writing anything about that weekend. It wasn’t a horrible experience because I got to talk to people I don’t see very often and hang out with my friends, but overall I wouldn’t say it was a good weekend for me.

If you’re really that curious about what happened though, here’s the short version:

Thursday: The day before the PC, I wake up with a head cold. Due to attempted terrorist attacks, airport security makes me throw out any “liquids, gels, or creams” that I have in my carry-on. That means no toothpaste, no deodorant, no shampoo, etc. When my mother and I finally arrive in Indianapolis, we have to go out and buy all the stuff we had to throw away at the airport. Not fun.

Friday: I play a bad build of Checkmate / Villains United, start out 2-0, and then end up losing to both bad draws and play mistakes to finish at an extremely disappointing 4-6. Two of my teammates make Day 2 with a 6-4 record playing the exact same deck. I feel jealous and inept.

Friday: I play a bad build of Checkmate / Villains United, start out 2-0, and then end up losing to both bad draws and play mistakes to finish at an extremely disappointing 4-6. Two of my teammates make Day 2 with a 6-4 record playing the exact same deck. I feel jealous and inept.

Saturday: Three of my teammates who failed to make Day 2 and I decide to enter the Team Sealed Pack $10K. The problem is, we have four total members, and we need to break up into teams of three. No one volunteers to sit out and play in the Scholarship Circuit, so we recruit two other guys (we’ll call them player A and player A’s friend) to make two teams of three. We name our teams NQG 1, which is comprised of my teammates Josiah and Joe, as well as player A’s friend; and NQG 2, which has me, my teammate Hal, and player A. After round 4, NQG 1 drops with a 1-3 record; apparently player A’s friend isn’t very good at Sealed Pack and made a few costly mistakes. Team NQG 2 starts out 3-0; then goes 0-2 and is forced to win out to have any shot at Top 8. We get our second Sealed pool, make much better decks than the first time around, and start out 1-0 to put us at a decent 4-2 record. Then, player A loses the deciding third game in our round 7 match against eventual $10K champions Kings Games; he could’ve won had he not forgotten to bounce The Calculator, Evil Oracle back to his hand before playing The Calculator, Crime Broker. This really makes everyone mad, but there’s a really small chance that if we win out we can Top 8 with a 6-3 record. We end up winning our remaining two rounds, and everyone is celebrating before the final standings even go up. As it turns out, we finished in 11th place after already being in 11th and winning our final match.

Sunday: One of my teammates who Day 2’d the Pro Circuit came in 72nd place to earn $630. After team splits, I’m left with $10.50, which is the grand total that I have to show for my weekend. I don’t feel like playing in any of the PCQs on Sunday, and my mom just wants to go home, so we check out of our hotel and leave to catch an earlier flight home. About an hour after I’m back home and settled in, my cold goes away almost instantly.

Writing that was painful enough; I don’t think I could psychologically handle revisiting the specifics of what happened throughout that weekend. If you were looking forward to a more elaborate tournament report, sorry to disappoint, but it’s not going to happen. However, this article still needs to be about something, because I obviously can’t get away with writing a half-baked tournament report that’s mostly me complaining about how bad I am at this game. I could continue my Deck Analysis series and review the remaining DC Modern Age decks, but the only new decks in the PC Top 8 were “Magic Tricks” and Secret Society control, and I don’t feel qualified enough to tell you how to play them. I could launch straight into a Golden Age Deck Analysis series, but it’s a little early to be thinking about PC: LA, and I don’t have any idea what to write about. Thus, I’m going to take a break from the usual and talk about a format many people are excited about but haven’t experienced firsthand: Team Sealed Pack!

Instead of doing an actual tournament report on the Team Sealed Pack $10K, I’m going to talk about specific aspects of the format that make it different from regular Sealed Pack. It’s a general consensus among players that Sealed Pack requires much more skill than Constructed, and Team Sealed Pack takes that to the next level by throwing in extra factors to consider while building decks and playing. I know I said I didn’t want to write about anything that happened during the weekend of PC: Indy, but this format is just too amazing for me not to say anything about it. Team Sealed Pack is easily the best sanctioned format Upper Deck has created since the first Golden Age, and I’m really grateful that I got to play in the format’s inaugural event (even if it was because I didn’t Day 2 the PC).

Building Your Three Decks

The most important aspect of Team Sealed Pack is deck construction. In normal Sealed Pack, deck construction is relatively simple; you just sort the characters you’ve opened, go into the team with the strongest character base, add generic attack pumps, and splash other characters to fill holes in your curve. It’s easy to cut cards, because if they don’t fit into your deck’s theme, then there’s no reason for you to consider playing them. However, in Team Sealed Pack, you can’t automatically deem a card unplayable, as it may fit into one of your teammate’s decks while being horrible in yours. There are a few different strategies and plans teams use when building their decks, but the two main ones are:

1) Create three decks of equal power level.

2) Create two strong decks, and use your leftover cards to make your third deck, which will be considerably weaker than your first two.

I know there hasn’t been much experience with the format as a whole (my opinion is based on the findings of only a single tournament), but I think the best strategy to use is number two. The first strategy doesn’t exactly work, because it’s extremely rare that you receive the right amount of cards to support three separate affiliations on almost the exact same level. Players believe that you can “control” how strong your decks are by shifting certain cards between decks, but in reality this doesn’t work. If you open your ten packs, and you’re gifted with a nuts Checkmate pool, a decent Villains pool, a decent Shadowpact pool, and a subpar JSA pool, you can’t force JSA to be better by taking away some of Checkmate’s good cards and throwing them into JSA. If the power level of your affiliations is unbalanced, the only real way you can balance them is by choosing not to play some of your power cards (but this is obviously a bad choice, as you never want to opt not to play good cards). Forcing equilibrium within your pool will only result in your team creating three under-powered decks, so it’s better to play the one or two great decks you received and make your last deck with whatever is left over.

With 140 cards, your options about what decks to build may seem as wide open as they can be. While this is certainly true, you’re generally restricted to playing two mono-team decks and one team-up deck due to the nature of the format. You can’t overlap team affiliations because it’s less than optimal to have two of your decks feeding off the same pool of characters. Your two strongest character pools can usually stand on their own, meaning your two best decks will be mono-team, and the leftover teams can be smashed together to form a decent curve that generally has no holes. No specific team is really better than any of the other ones, so build your decks based on the pool you open and not the specifics of what team you’re playing. It’s hard to go into the gritty details of deck construction when I don’t have an example pool as a visual aid, so the best generic advice I can offer is to not force things your pool can’t support, and to do your best to stay mono-team with your two stronger decks to prevent an overlap in your character selections.

The Leftover Deck

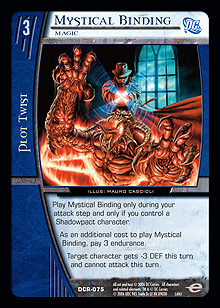

The two strong decks should almost always build themselves. If you open some of the “bomb” cards in a set, then you automatically know to build a deck around those cards’ teams so you can get the most out of your powerful effects. The real challenge in Team Sealed Pack deckbuilding is deciding how to build your leftover deck. Keep in mind that the leftover deck doesn’t have to be bad, but it’s always going to be less focused than your other two decks. I think the most effective leftover deck you can build is one with a solid curve and generic attack pumps as plot twists. You can argue that generic attack pumps are more important for your two strong decks, but you should have enough team-stamped pumps to not even need to run them. For example, if your pool allows you to play Shadowpact and Checkmate as your two strong mono-team decks, you’re probably going to have some Mystical Bindings and Brother Eyes that you can use as your main ATK pumps. Even if you open I Still Hate Magic! or Blinding Rage, your strong decks won’t really need to play them because they have their own attack pumps that function just as well. If you make your leftover deck a generic beatdown deck with solid characters and good attack pumps, you will be able to beat decks that are more focused than yours simply by hitting your curve.

The two strong decks should almost always build themselves. If you open some of the “bomb” cards in a set, then you automatically know to build a deck around those cards’ teams so you can get the most out of your powerful effects. The real challenge in Team Sealed Pack deckbuilding is deciding how to build your leftover deck. Keep in mind that the leftover deck doesn’t have to be bad, but it’s always going to be less focused than your other two decks. I think the most effective leftover deck you can build is one with a solid curve and generic attack pumps as plot twists. You can argue that generic attack pumps are more important for your two strong decks, but you should have enough team-stamped pumps to not even need to run them. For example, if your pool allows you to play Shadowpact and Checkmate as your two strong mono-team decks, you’re probably going to have some Mystical Bindings and Brother Eyes that you can use as your main ATK pumps. Even if you open I Still Hate Magic! or Blinding Rage, your strong decks won’t really need to play them because they have their own attack pumps that function just as well. If you make your leftover deck a generic beatdown deck with solid characters and good attack pumps, you will be able to beat decks that are more focused than yours simply by hitting your curve.

Who Plays Which Deck?

Another big question in Team Sealed Pack is deciding which team member plays which deck. These are the two main philosophies about play ability and how it affects which deck each player ends up piloting:

1) The “best” player on the team should play the “worst” deck because he or she can do more with it and win games against better decks simply by outplaying opponents.

2) The “worst” player on the team should play the “worst” deck because if the two best players are playing the two better decks, then they have a much better chance of winning all of their games.

When playing in a team event, the last thing you want to have is an ego. If it’s determined that you’re the “worst” player among your teammates, don’t take it personally; being deemed the “worst” player on the team in no way, shape, or form means you’re a bad player. For example, let’s say for some reason Alex Brown and Doug Tice, two of the best Sealed Pack players in the world, need me as the third member on their team. Now, it’s obvious that I’m not as good as them, so I would be considered the “worst” player on the team. However, this doesn’t mean that I’m a bad player; it just means that comparatively, my teammates are better than I am, and I have to accept that and play to the best of my ability nonetheless. Don’t waste time arguing over how you rank among your teammates in terms of Sealed Pack skill. If you know that your two teammates are better than you, it’s best that you announce it as soon as you begin building your decks so you don’t get into a conflict over it. If all else fails, you can always determine the “positions” within your team based on your rating.

The big mistake my team made in the $10K was using the second strategy and giving our “worst” player the worst deck. This doesn’t sound like such a bad plan, but what ends up happening is the worst player always loses, which forces the other two team members to win both of their games every single match. Sometimes you can get lucky and have your worst player end up playing the player on the opposite team with the best deck (and lose a match he or she could never win anyways), but generally you’re putting your team at a disadvantage by giving the worst player the worst deck. If a player cannot rely on play skill to win games, then he or she has to rely on his or her deck. However, if you give the player a bad deck, then there’s an extremely small chance the player will win any of his or her games. This forces the two better players to pull the team by winning every single one of their games, and being under that much pressure is never a good thing. You should make sure that each member of the team has at least some chance of winning his or her match, so the most logical thing to do is balance the scales. In my opinion, it’s best to give your best player the worst deck, because he or she can make up for the deck’s lack of focus or stability with his or her ability to make smart decisions and outplay opponents. The best deck should play itself, so if you give your worst player the best deck, he or she won’t have any trouble playing it and will win most games due to the quality of the cards.

Teamwork!

My final piece of advice about Team Sealed Pack is to make sure you and your teammates are capable of cooperation. Even though every game you play is just between you and your opponent, teamwork factors into this format much more than it seems. When building your decks, make sure you communicate with your teammates about your decisions on what cards you’re playing. Before you register anything, always go over all three of the decks as a team, because if one player misses an important card that should be included, there’s a good chance one of the other two players will catch it. Discuss your opinions on specific card choices, character ratios, and anything else that may come up. Building your decks individually is the worst thing you can do; you should always take advantage of the fact that you have three different minds that can work on the same problem. Make sure when you form your team before the tournament that you know you can trust your two teammates, and make sure that each individual member can pull his or her own weight. It’s easy to sit back and not contribute to deck construction when there are two other people doing most of the work for you, but in the long run it will hurt the team as a whole because you won’t be on the same page about things.

My final piece of advice about Team Sealed Pack is to make sure you and your teammates are capable of cooperation. Even though every game you play is just between you and your opponent, teamwork factors into this format much more than it seems. When building your decks, make sure you communicate with your teammates about your decisions on what cards you’re playing. Before you register anything, always go over all three of the decks as a team, because if one player misses an important card that should be included, there’s a good chance one of the other two players will catch it. Discuss your opinions on specific card choices, character ratios, and anything else that may come up. Building your decks individually is the worst thing you can do; you should always take advantage of the fact that you have three different minds that can work on the same problem. Make sure when you form your team before the tournament that you know you can trust your two teammates, and make sure that each individual member can pull his or her own weight. It’s easy to sit back and not contribute to deck construction when there are two other people doing most of the work for you, but in the long run it will hurt the team as a whole because you won’t be on the same page about things.

The members of team Kings Games, the winners of $10K Indy, are a great example. They created a simple series of signals to help control the draft, and while their opponents thought it was ridiculous at first, they quickly realized that the team’s communication medium was giving them a huge advantage. In the end, teamwork prevailed, and I believe Kings Games won the tournament because they mastered the concept of having three separate sources of information and ideas come together as one. I can’t wait for the next Team Sealed Pack event. I hope it’s an independent $10K, not one attached to a Pro Circuit, so more players can play in it and be better prepared for it. If you can get a few other people together at Hobby League, for instance, you should try playing Team Sealed Pack. It’s not only a very skill-intensive format, it’s an extremely fun one as well! I urge everyone to try it out; you’ll be hooked after your first Sealed pool.

Please send all requests to gvl@nc.rr.com, and as always, questions, comments, suggestions, and complaints are welcome.