|

The Sentry™

Card# MTU-017

While his stats aren’t much bigger than those of the average 7-drop, Sentry’s “Pay ATK” power can drastically hinder an opponent’s attacking options in the late game.

Click here for more

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

“You’re food now, shirt!” —Suggested alternate flavor text for Charaxes (who was formerly Killer Moth)

To me, the Arkham Inmates are all about fun. That’s not to say I don’t think they’re a good team for high-end playability, just that when we were making them, we really wanted them to come off as a blast to play. (Unlike the Sentinels—we want playing them to be a chore.*) Don’t get me wrong—I’m only saying we wanted them to be a blast for you to play, not for your opponent to play against. In fact, earlier this week I watched a guy get crushed by an Arkham deck so badly he started weeping tears of blood. (Then again that happens a lot around here. It’s just something that we do.) To me, the Arkham Inmates are all about fun. That’s not to say I don’t think they’re a good team for high-end playability, just that when we were making them, we really wanted them to come off as a blast to play. (Unlike the Sentinels—we want playing them to be a chore.*) Don’t get me wrong—I’m only saying we wanted them to be a blast for you to play, not for your opponent to play against. In fact, earlier this week I watched a guy get crushed by an Arkham deck so badly he started weeping tears of blood. (Then again that happens a lot around here. It’s just something that we do.)

Before the DC set came out, there was a lot of chatter on the boards about what the Arkham team was going to be like. (You know, like what their focus was going to be, like how the Fantastic Four are good with equipment, or how the Brotherhood is good at dominating metagames.) One popular theory was that Arkham was specifically not going to have a focus. They were going to be a random collection of crazies with no rhyme or reason tying them to each other. They would be a non-team team (kind of like the opposite of the unaligned guys who, through enablers like Mojo or Deathstroke, can actually function like a real team).

The funny thing about that theory is that early in preliminary design, we actually considered the very same thing. We tossed around the idea of intentionally forcing a lack of synergy between any of the Arkham characters just to up the chaos factor. In fact, at one point we considered making Arkham the only team whose members couldn’t team attack or reinforce one another. But there was a problem (as there usually are in these kinds of stories—I mean, how interesting is a story that’s like, “Yeah, so we came up with this idea, and it was good, so we tried it, and it worked, and we were done”?).

The problem was that, intentional or not, there will always be synergies or cards that work well together in a large enough collection. What I mean is, sure if you look at two cards in a vacuum, there might not be any synergy directly between them. But if you add in a third card, you have to check all three against each other. As you add more and more cards, natural synergies become impossible to avoid especially if you allow other cards to connect them. For example, there may be no obvious synergy between Storm, Ororo Munroe and A Child Named Valeria, but once you add in cards like Invisible Woman, Sue Storm and a bunch of small, front row FF characters, Storm’s ability to prevent opposing characters from flying over your reinforced, unstunnable little dudes creates a lock on the board.

The point is, it’s actually really hard to avoid creating synergies or to actively combat them, and even if we could, it probably wouldn’t be that much fun anyways, since so much of deck design is finding synergies. The good news is that there were lots of other ways to make Arkham feel chaotic (and that’s the real rub—it’s not important to make the inmates actually chaotic, it’s only important to make them feel chaotic). The point is, it’s actually really hard to avoid creating synergies or to actively combat them, and even if we could, it probably wouldn’t be that much fun anyways, since so much of deck design is finding synergies. The good news is that there were lots of other ways to make Arkham feel chaotic (and that’s the real rub—it’s not important to make the inmates actually chaotic, it’s only important to make them feel chaotic).

One mechanism we decided to go with is randomness. By nature, a card game is random (unless you’re a big cheater monkey you randomize your deck before the game begins). Therefore, we usually don’t want to add too much more randomness, because if things get too random, good decision-making no longer has enough of an impact on the game. However, for some of the Arkham characters, it just seemed too appropriate. I mean, who could resist making Two-Face a coin flip card? It just felt right to give The Joker, Laughing Lunatic, a “pick-a-card” mechanic. For curve-smoothing, we felt that the draw-a-new-hand mechanic captured the chaos of a Prison Break.

A second way we introduced controlled chaos was through mini-games like the Riddler’s power and Riddle Me This. These effects take a quick break from the main game as one player assumes the role of master criminal and the other, hapless victim.

Discard effects in general became a theme of Arkham’s, both because it fit their propensity for stealing and because it made a nice foil to the Gotham Knights’ card-drawing power. It’s worth noting that Museum Heist (in all its horrible-pun-in-the-flavor-text glory) was originally an Arkham-only card, but was made generic when we added the more chaotic Cracking the Vault to the Inmates’ repertoire.

A larger mechanic that was introduced to the team slowly over the course of general design was Arkham’s ability to punish exhausted characters. To me, this represents their ability to take advantage of when the good guys (in this case, the characters controlled by the opponent) are caught napping. This theme is divided into enabler cards (cards that facilitate exhausting opposing characters) and punisher cards (cards that, uh, punish exhausted characters).

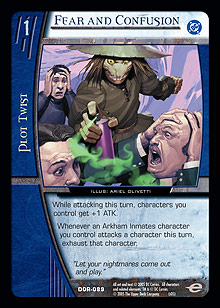

Fear and Confusion and No Man’s Land function as enablers, but you should notice that both are only useful during your attack step. The ability to exhaust a character before its controller has had a chance to attack with it can be pretty devastating, and because it feels more controlling than chaotic, we decided to regulate Arkham’s enabler cards’ usage. Fear and Confusion and No Man’s Land function as enablers, but you should notice that both are only useful during your attack step. The ability to exhaust a character before its controller has had a chance to attack with it can be pretty devastating, and because it feels more controlling than chaotic, we decided to regulate Arkham’s enabler cards’ usage.

Once we had the enabler cards in place, we needed to come up with the punishers. We decided Charaxes was a scary enough guy that whenever he stunned an exhausted character, he would just eat it (which, due to the fact that nobody actually dies in comics, translates to that character getting KO’d). From the beginning, Arkham Asylum had two mechanical functions since it is both the bad guys’ common “home” as well as their prison. Its return-to-hand mechanic represents the bad guys getting taken off the streets (while still threatening to return), and its ATK bonus symbolizes the crazies running amok on the unsuspecting and/or unprepared populace.

Clayface’s flavor is a bit subtler. We wanted his stats to fluctuate to represent his constant shape-shifting and resizing. Keying his numbers off of opposing exhausted characters seemed like a nice fit, especially given that he often operates in disguise and catches people unawares. It was a tough decision whether or not to give him range. He can project himself pretty far, but it was still on the bubble given our stringent policy on doling out range (remind me to tell you about it sometime). Ultimately, we felt that while range often strengthens a character, it was especially useful for Clayface to hide in the support row (forcing an opponent to exhaust at least two characters to get to him) while threatening an attack if he survives to his controller’s attack step.

A couple other characters that indirectly tie into the exhaust mechanic are Mr. Freeze and Poison Ivy. While neither of them actually exhausts an opposing character or gets bonuses from combating one, Mr. Freeze keeps a character from readying for the next turn (acting as an enabler for the next turn), and Poison Ivy goes one better by keeping one stunned (and consequently exhausted) next turn—and that’s only if its controller chooses to “recover” it.

You may have noticed Lockup, an unaligned character, shares the punish-exhausted-characters mechanic. It’s because originally he was on the Arkham Inmates roster. Unforunately, DC Comics told us he wasn’t really appropriate as an Arkham character, so we moved him to unaligned. (Have I mentioned they send us comic books?)

Another mechanic we introduced with the Arkham team is characters that do something while they’re in your hand. You can discard perennial sidekick cards like Harley Quinn and Query and Echo to pump up their “bosses.” The secondary in-hand power gives added utility to characters that are only good at certain times of the game or in specific situations (for example, in most non-weenie decks, 1-drops are only really only good on the early turns). Unofficially we were originally calling it the “flunky” or “sidekick” mechanic, but it has made its way into later sets onto characters that aren’t just sidekicks, so we’re probably going to have to come up with a better name for it. Another mechanic we introduced with the Arkham team is characters that do something while they’re in your hand. You can discard perennial sidekick cards like Harley Quinn and Query and Echo to pump up their “bosses.” The secondary in-hand power gives added utility to characters that are only good at certain times of the game or in specific situations (for example, in most non-weenie decks, 1-drops are only really only good on the early turns). Unofficially we were originally calling it the “flunky” or “sidekick” mechanic, but it has made its way into later sets onto characters that aren’t just sidekicks, so we’re probably going to have to come up with a better name for it.

Okay, that’s all I got for this walk through the Asylum. Now for a public service announcement.

Several weeks ago, I asked people to send me questions that I could answer in a future article. Well, next Friday, I’ll tackle a whole bunch of ’em. Also, to anyone who’s emailed me in the last few weeks but hasn’t yet received a reply, thank you, and you’ll be hearing from me sometime this coming week.

Send questions or comments to dmandel@metagame.com.

*Just kidding. I figured it’s been a while since there was any controversy about R&D’s bias against everybody’s favorite** robots.

** I know, I know—they’re not everybody’s favorite. Matt Hyra, for example, hates them. Just the other day he was like, “The Sentinels suck. We shouldn’t print any more.” And I was like “No way, man, the Sentinels rock! They’re steady! They’re steady rockin’ all night long!” And he was like “Nuh, uh,” and then he went on, but I didn’t hear because I was eating a sandwich***.

*** Okay, I wasn’t actually eating the sandwich. I was just pretending so Hyra would stop talking to me.

|

| |

| Top of Page |

|

|

|

|

|