Games of Vs. System ultimately tend to come down to who is getting the most out of their resources. Each player draws two cards per turn and gains an escalating number of resource points per turn. These are the currency with which you buy victory, and if squandered, it will surely mean defeat.

Different decks attempt to do this in different ways, but ultimately, everyone is looking to get the most bang for their buck. Squadron Supreme takes the “live fast, die young” approach, looking to burn through all of its cards as quickly as possible and ultimately kill opponents pretty quickly. Any cards left in opponents’ hands that were kept there for the later game (for example, high-cost characters) become a waste against a really fast Squadron draw. You can’t take it with you, and Squadron Supreme does its best to waste opponent resources by never letting them become relevant.

Meanwhile, slower control decks look to brick-wall and get access to extra resources as the game goes longer. With more resource points and more opportunities to do things in the form of more cards, decks like X-Stall and New School get their advantage from playing for late game value. They aren’t really looking to do anything but invest in the future, hoping that (should they get there) they can produce something that will offset any early beats and that cannot be matched in terms of raw card-for-card quality by anything brought to the table by faster decks.

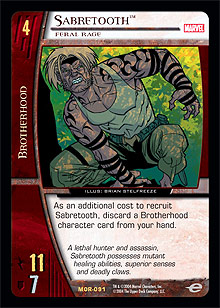

Regardless of the game plan of a deck, it will likely contain the most “efficient” possible cards with which to execute its nefarious schemes. It didn’t take players long to realize that characters like Sabretooth, Feral Rage, who is simply colossal for his cost, are a good choice for beating down, while that little joker Dr. Light, Master of Holograms shines out as being worth far more than a paltry 3 resource points when he (over the course of a game) in effect produces another 6 or 8 on his own. Characters represent investments in terms of resources. You spend them on something that you anticipate will have its effect over a few turns as part of a growing attempt at board advantage. This is why cards like Finishing Move are so powerful in both Sealed Pack and Constructed. They take what might have looked like a sound investment and leave it dead in the water (or in this case, the KO’d pile).

Regardless of the game plan of a deck, it will likely contain the most “efficient” possible cards with which to execute its nefarious schemes. It didn’t take players long to realize that characters like Sabretooth, Feral Rage, who is simply colossal for his cost, are a good choice for beating down, while that little joker Dr. Light, Master of Holograms shines out as being worth far more than a paltry 3 resource points when he (over the course of a game) in effect produces another 6 or 8 on his own. Characters represent investments in terms of resources. You spend them on something that you anticipate will have its effect over a few turns as part of a growing attempt at board advantage. This is why cards like Finishing Move are so powerful in both Sealed Pack and Constructed. They take what might have looked like a sound investment and leave it dead in the water (or in this case, the KO’d pile).

Plot twists fill an interesting roll. They are “spent” immediately, and, in a raw numbers sense, they are much less likely to do as much to finish off an opponent as any single character that sticks around. So why would anyone play them? The answer becomes obvious pretty quickly. When players are devoting themselves to investing as best they can in a strong board presence, it can be hard to develop any real board advantage because similar beefy characters are bumping against each other. Assuming that neither player is unlucky with draws, there is limited potential for any one deck to assert itself and get a winning edge from curving out against an opponent doing the same. But plot twists do just that.

In a game of baseball, at the most basic level, every batter is looking to hit a home run, every pitcher is trying to pitch a no-hitter, and every fielder is looking to make the catch and get some outs (so that they in turn can start hitting homers). This is why, at the most basic level, baseball is pretty boring. It is why football (proper football, with round balls and the World Cup) is a bit dull. Every golfer wants to get the ball into the hole. Yawn.

What makes things interesting is that, while the goals of sportsmen are transparent, the method of getting a winning edge is not necessarily so straightforward.

A pitcher is playing a game against a batter. They are trying to force people who hit balls for a living either to swing and miss, or to swing and hit the ball the wrong way such that it is caught or allows one of the players on base to become an easy out. Sometimes this means a slow curveball, sometimes a fastball. The changeups are where things get really interesting.

In football, it isn’t simply a race to attack an opposing team’s goal at every juncture. Some teams play very defensively, patiently waiting for one opportunity to send a quick striker through on a counterattack after having fended off an overcommitted opposing strike. Some will play for fouls and set pieces in dangerous areas of the field, working a great endgame at the end of their free-kick taker’s legs.

Even in golf, in match play, there is a whole psychological element to the game. Players look to generate psychological advantage hole by hole as much as they look to get the ball into the hole in the fewest possible strokes.

Plot twists are these little games. As their name suggests, they can twist the outcome of an encounter such that whatever is on the board isn’t necessarily a clear indicator of who’s winning, or as permanent a fixture as some players might like. The fact that they do double duty in either the hand or the resource row also makes them the most efficient things to put in the row, where they’ll be ready for whenever they might be needed.

One resource that is talked about a little less is endurance itself. In some respects, this is kind of funny, as ultimately it is the most important resource of all. Without it, you lose. However, until the point that you don’t have any, your endurance total typically doesn’t do anything at all. For a long time, players have sneered at cards dedicated to gaining endurance. After all, if the game ends with you on more endurance than your opponent, and the difference in endurance is greater than the amount that you gained, the card you played did nothing. It did not advance your goal of lowering your opponent’s endurance to 0 in the slightest, but it did count as one of your cards drawn. Imagine that you switched that card for a Surprise Attack. Spending a card to have no effect on the board or your amount of potential resources is pretty awful, but if it kills someone, that is fair enough. Endurance gain cards are never going to do that. They are the ultimate in investment cards; you play them in the hope that they will keep you alive long enough to see more cards and get you to a point where you can play finishers efficient enough to make up for having devoted those card slots to endurance gain earlier on.

In Atlanta, Nick Little had a Mental deck that ran Eye of the Storm, the ultimate “do nothing, gain a little endurance” card. In his deck, it even worked. In a format replete with rush decks like Squadron Supreme, he needed a little edge to take him into the mid- and late game, and a little endurance gain was just the ticket. Of course, with Emma Frost, Friend or Foe, he could get extra mileage out of it, but in and of itself, it actually fitted very neatly into the deck’s overall strategy.

In Atlanta, Nick Little had a Mental deck that ran Eye of the Storm, the ultimate “do nothing, gain a little endurance” card. In his deck, it even worked. In a format replete with rush decks like Squadron Supreme, he needed a little edge to take him into the mid- and late game, and a little endurance gain was just the ticket. Of course, with Emma Frost, Friend or Foe, he could get extra mileage out of it, but in and of itself, it actually fitted very neatly into the deck’s overall strategy.

Normally, endurance gain needs to be tacked onto a card that is broadly useful before the endurance gain. Drain Essence, X-Statix HQ, and Katma Tui are all pretty reasonable before they gain you any endurance, either via another effect they perform or simply because they’re a warm body for attack or (more likely) defense. Gaining endurance is a support function of a deck looking to “go long.”

Where things get really interesting is in the spending of endurance. Before Crisis came out, the opportunities to use endurance as a resource to activate effects were pretty few and far between. Garth ◊ Tempest, Atlantean Sorcerer was always a winner, but after him, the options got a little tricky. Punisher’s Armory and Witching Hour both allowed for some pretty nifty effects, but the amount of play they saw was a little bit limited. It seemed that the real hour for witches and wizards was a little later in coming. With the Shadowpact team, suddenly players had to decide what value they placed on various common in-game actions in terms of their own endurance and build their Magical decks accordingly.

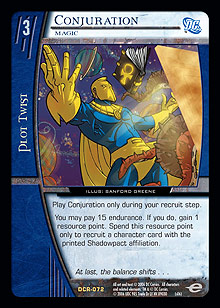

Pro Circuit San Francisco is approaching rapidly now, and I must confess to being highly intrigued as to how much magic we will be seeing in this new format. Is 15 endurance too much to pay to get a whole turn ahead on the opposition? If endurance is normally a measure of time until the game is over, is 15 endurance more or less than a turn? What factors can affect the answers to these questions? I have been pondering such things ever since cracking a Conjuration in the first pack of my first Crisis Draft. It felt to me like playing a 4-drop two turns in a row was pretty good, but then in my next Draft, I played back-to-back characters with Tricked-Out Sports Cars on them on turns 2 and 3, putting me well ahead in resource points on the board without the cost of endurance.

Pro Circuit San Francisco is approaching rapidly now, and I must confess to being highly intrigued as to how much magic we will be seeing in this new format. Is 15 endurance too much to pay to get a whole turn ahead on the opposition? If endurance is normally a measure of time until the game is over, is 15 endurance more or less than a turn? What factors can affect the answers to these questions? I have been pondering such things ever since cracking a Conjuration in the first pack of my first Crisis Draft. It felt to me like playing a 4-drop two turns in a row was pretty good, but then in my next Draft, I played back-to-back characters with Tricked-Out Sports Cars on them on turns 2 and 3, putting me well ahead in resource points on the board without the cost of endurance.

All of a sudden, players have a whole new resource to play with. I really hope they have fun.

Tim “Two Turns Ahead, 30 Endurance Behind” Willoughby

timwilloughby@hotmail.com

This article was brought forth by the following two ideas: First, I am going to my very first baseball game in San Francisco, and I felt that I had to get an idea of what (beyond the potential to sit around with a drink or two for hours) made the game so good. Second, I have come to realize that if most things I do in my life are a function of time and money, for the first time I have more of the latter than the former. Due to work commitments, it looks unlikely that I will make another Pro Circuit after San Francisco this year. Luckily, I have quite a bit of money at a good exchange rate with which to enjoy the Californian summer Pro Circuit. It will be good times.