|

The Sentry™

Card# MTU-017

While his stats aren’t much bigger than those of the average 7-drop, Sentry’s “Pay ATK” power can drastically hinder an opponent’s attacking options in the late game.

Click here for more

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Last week, I talked about different kinds of metagames. Today I'm going to take a look at how design and development help shape the metagame as well as how the metagame affects design and development.

Coming to Terms

For the purposes of this article, I'm defining the term "environment" as the set of available cards from which a player can build decks as well as the potential decks that can be built therein. And I'm defining the term "metagame" as which decks are popular and in what volume those decks are getting played.

Also, this column is looking at design and development with regards to keeping the metagame—especially the tournament metagame—healthy. There are many other issues design and development take into account when working on a set, not the least of which are the casual player's view or the collector's perspective.

Overview

Design generates a card pool, and development polishes it up into a finished set. The set is inserted into the environment, and that, combined with players' choices, determines the metagame. Design and development pay careful attention to the metagame (although for different reasons) and use what they learn in the future when generating and polishing up a new set.

Let me break that down.

Design Generates a Card Pool Design Generates a Card Pool

Design and development shape the environment by setting up parameters for the card sets. One way of looking at it is that design determines what type of cards are in the environment while development determines how powerful those cards are. (In reality, the whole process is organic, with design and development working closely together. However, one of the goals of this column is to demonstrate some of the differences between design and development.)

Design sets up the parameters of what kinds of cards can exist in an environment. In a lot of ways, the Vs. System is like a set of checks of balances. For a given strategy, there is a counter strategy. But what if that weren't true? Let's say that X-Men weenie swarm is the most overtly powerful deck available. However, it curls up and dies to a Flame Trap. Therefore, if it gets very popular in the metagame, players will start packing the Trap. But what if design decided not to put Flame Trap into the set? Suddenly, the X-Men deck's check would be absent. Perhaps the deck would become unstoppable and end up dominating the metagame.

One deck that's getting a decent amount of notice on the various fan sites is "Turbo Alicia," a Fantastic Four deck built around jumping the resource curve by using Alicia Masters (and possibly Cosmic Radiation) to recruit a large Human Torch or Thing early in the game. But what if Alicia had never been printed? An entire archetype would cease to exist because the engine around which it was built would be gone.

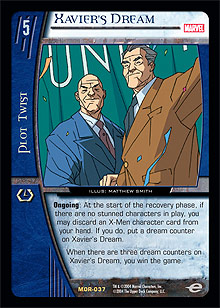

When examining a card pool, it's natural for a player to pick out the cards that define just what can or cannot be done. Cards like Flame Trap, Alicia Masters, Beast, Doomstadt, or Xavier's Dream are all examples of cards that push the envelope of what can be done in the game.

One of design's goals is to keep the metagame healthy by giving players lots of options, which in turn fosters the existence of many deck archetypes. In future articles, I'll go over some of the tools design uses to that end. For now, all that's important is the point that design sets up the parameters of types of things can or cannot be done in an environment.

Development Polishes It Up Development Polishes It Up

Right now, Brotherhood rush decks are popular, at least partly due the strength of the ongoing plot twist The New Brotherhood. Foiled is the only card in the environment that can KO an ongoing plot twist, but since Foiled has a pretty hefty restriction (your deck must be prepared to function with an interrupted character curve), it will probably only make the cut into a select group of decks. However, what if design had submitted this card instead of Foiled?

Mean Foiled

Play Mean Foiled only from your resource row.

KO target ongoing plot twist.

It looks, the same, but there's a crucial difference. Unlike its friendlier counterpart, Mean Foiled doesn't KO itself. Suddenly the environment has an ongoing plot twist control that not only leaves your resource row intact, but also stunts your opponent's growth. If Mean Foiled existed, the Brotherhood decks would either leave The New Brotherhood out or run the risk of falling way behind on the resource curve.

The problem is, Mean Foiled's existence in the environment could preclude players from running any ongoing plot twists. This would be an example of a micro-metagame like I discussed last week, although with much bleaker ramifications. Mean Foiled single-handedly makes an entire class of cards useless or even detrimental for a player to have in his or her deck. This is bad. This is also where development comes in.

If design defines the parameters of what can be done, development defines the parameters of how well it can be done. Since one of development's goals is to keep the metagame healthy by keeping the power level of cards under control, a card like Mean Foiled would be a big no-no.

The Environment, Combined with Players' Choices, Determines the Metagame

This part is what I talked about last week. Effectively, players explore the environment and start building decks. Some of these decks become more and more popular until the metagame begins to take shape. Occasionally a big tournament will alter the popularity of the decks or possibly introduce a previously unknown archetype into the mix.

Design and Development Pay Careful Attention to the Metagame Design and Development Pay Careful Attention to the Metagame

The Marvel TCG (as well as the Vs. System) is brand new. Not only is the game engine a new world for players to explore, but players have only had a month to learn and try out all the cards. Even still, the metagame has already started taking shape. I've read about X-Men weenie and control decks, Fantastic Four beatdown and equipment decks, Brotherhood rush decks, Sentinel swarm decks, Doom control and combo variants, and even some Mojo/Punk and Xavier's Dream decks, not to mention a bunch of multi-team hybrid decks. All in all, there's some exciting stuff out there. But as robust as the metagame is now, two things are certain.

1. Large tournaments can, and often will, redefine the metagame. It's human nature for players to want to play the most successful decks.

2. When the DC Origins set hits the shelves, the metagame is going to get shaken up again. Trust me, there's some chewy goodness in there.

But I'm getting off topic. The important point to take from all this is that while the metagame goes through its twists and turns, design and development will be watching.

(Although for Different Reasons): Design Watches for the Focus

When two decks face off, there is usually a focal point of conflict dependent on the matchup. For example, in the X-Men weenie versus Doom control match-up, the central point of conflict might be whether the X-Men player can muster enough offense fast enough to win before the Doom deck asserts control. However, in the X-Men weenie mirror, attrition plays a larger role, and the point of conflict might be which player can better protect his or her Blackbirds. In the Doom mirror, games tend to run long, so it might come down to which player draws or recycles more Gamma Bombs.

Just as a given match-up can have a focus, so can the metagame itself. Design watches the metagame to see what kinds of decks are getting played. Are the decks built around speed? Board control? Card combos? Alternate victory conditions? Design wants to understand what the focus (or foci) of the metagame is so it can mess with that focus in the future. One of design's jobs is to keep the game fresh, and one of the tools that design uses to that end is to periodically shake things up.

(Although for Different Reasons): Development Watches Relative Power Levels

In a lot of ways, development acts as a policeman, making sure that nothing gets out of hand both at an individual card level as well as a team by team level. In a perfect world, while each team would have its own strengths and weaknesses, every team would be at the same relative power level. Unfortunately, it isn't a perfect world.

There's been a lot of talk on the forums about how balanced Marvel is. For the most part I agree, however I'm going to let you in on a little secret: We don't control the metagame.

While the development team tests many different types of decks (our testing gauntlet mirrors reality pretty well) we can't predict with 100 percent accuracy what players will do with the cards once they hit the streets. Here's the upside: The fact that we don't control the metagame is a Good Thing. If we knew exactly what players could and would do with a given card pool, the game wouldn't be as much fun. Part of the joy of deckbuilding is the sense of exploration and discovery a player gets when looking through a new card set. How would you like it if you knew that every possible deck you might ever come up with has already been built and thoroughly tested? (This also touches on the issue of linear design versus open design, which I'll talk about in a future article.)

So okay, development doesn't control the metagame. What does it do?

As I mentioned before, it would be wonderful if every team were of exactly equal strength, but we know this cannot be the case. Part of the problem is there's no way to quantify how strong a team is. One could argue that the X-Men have the best cheap characters, the Sentinels have the best Army characters, the Fantastic Four have the best equipment enablers, Doom has the best plot twists, and the Brotherhood has the best direct endurance loss characters. Now how do we rank them in generic terms? As I mentioned before, it would be wonderful if every team were of exactly equal strength, but we know this cannot be the case. Part of the problem is there's no way to quantify how strong a team is. One could argue that the X-Men have the best cheap characters, the Sentinels have the best Army characters, the Fantastic Four have the best equipment enablers, Doom has the best plot twists, and the Brotherhood has the best direct endurance loss characters. Now how do we rank them in generic terms?

While we can't officially determine which teams are the best, the metagame is a great tool for development to get a sense of which teams players are favoring. When working on a new set, one of development's goals is to try to improve the weaker teams (and by weaker teams, I mean the teams that are not seeing much play), thereby making more teams competitive and breeding a healthier metagame. This is not to say that if your favorite team is currently very powerful, it's going to get hit by the nerf bat, just that it might not get the same sort of boost that a weaker team will.

Note: I don't want to oversimplify the design/development process. There are actually many more aspects of the metagame that are important; I just picked two of the big ones.

Use What They Learn in the Future

This is the part where I would go into specifics about how the current metagame is actually influencing our design and development decisions. Unfortunately, I can't go into details because that would ruin the surprise. However, in a few months, when the DC set hits the streets, I will fill everyone in on what was on our collective mind when we worked on the set.

I received some interesting emails discussing the metagame this past week. However, since this article has run a little long, I will post a couple of them next Friday so you can get a sense of what some players' local metagames are like. I'll also take a look at design and development from top (down) to bottom (up).

As always, send any questions or comments to dmandel@metagame.com.

|

| |

| Top of Page |

|

|

|

|

|